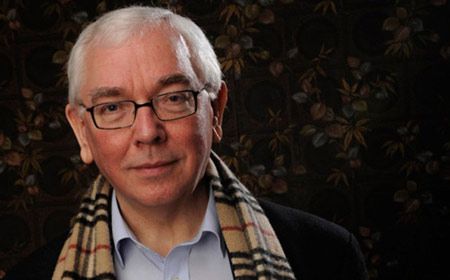

Our film specialist Gerard Elson chats with iconic director, Terence Davies.

Terence Davies’s The Deep Blue Sea – just his seventh feature film in 27 years – is an adaptation of Terrence Rattigan’s same-titled play from 1952, previously brought to the screen in 1955 by director Anatole Litvak. In it, Hester Collyer (Rachel Weisz), the wife of a loving yet passionless magistrate (Simon Russell Beale) embarks on an affair with a virile younger man, the former RAF pilot Freddie (Tom Hiddleston).

Both the play and Davies’ film begin with accounts of Hester’s failed suicide. Yet the two versions’ respective means of dramatising the scene couldn’t be less alike. Davies’ film opens with an inventory of Hester’s room and her moribund form, surveyed with fluid grace by a ghost-like camera as classical music keens on the soundtrack. Intercut with this is an extended shuffle through Hester’s memory bank. Barely a word is uttered for 15 minutes.

When contrasted with Rattigan’s more functional means of imparting the same narrative data (which Davies outlines below), the sequence proves instructive regarding the filmmaker’s own philosophy of film adaptation. (This I learned might be summarised as: ‘For god’s sake, make it cinematic!’)

What about Terence Rattigan’s play suggested to you it might be time it were dusted off and re-adapted for the screen?

Really, the play picked me. The Rattigan Trust came to me and said would I like to do an adaptation of one of the plays for his centennial, which was 2011. And I said, ‘Well, I can’t really do Separate Tables…’ because I thought the Burt Lancaster film at the end of the ’50s was really rather good. It would be in my mind equally difficult to do The Browning Version. I said, ‘I don’t think I can do that either, because Michael Redgrave gives such a wonderful performance [in the 1951 adaptation].’ So I read the whole of the canon. And I said ‘I think I can do something with The Deep Blue Sea.’

Had you seen the

My mother had taken me to see it in the mid-’50s. I was still at school. All I remembered was just one shot of Kenneth Moore coming down a staircase. I couldn’t remember anything else. I saw about 10 minutes on YouTube and it was basically a photographed play – not very good and not very good performances, I have to say! [Laughs]

So you didn’t feel the need to go back and see what they got wrong?

No, because then you have [that version] fixed in your mind rather than how I see the play. That’s what was difficult with Separate Tables and The Browning Version: I’ve got those films in my mind and I don’t think I could have done anything as good as that.

So there are certain things, then, that you would never re-adapt as you think they were so well-realised the first time around?

The only thing I wouldn’t touch with a barge pole is anything with violence in it, because my father was a very, very violent man and I just can’t watch it. I don’t want to make films that are violent. That’s the only thing that would put me off something. I was once sent a gangster script and I just said, ‘What do I know about the underworld?’ I don’t know about drug dealing – I just don’t.

I found

When I was growing up, my mum and my sisters took me to what used to be called a ‘woman’s picture’: things like All That Heaven Allows, Magnificent Obsession, Love is a Many-Splendored Thing. The central character was always a woman. And later, I discovered things on television like Letter From an Unknown Woman. The Heiress was another.

I suppose because that’s been put in me when I was a child, I am attracted to that kind of thing. But I would only ever do anything that I felt I could see and hear. If I can’t see and hear it, I’m not interested. These films happen to be about woman and what society does to them; that’s coincidental. In a way, if I could have seen The Deep Blue Sea from Freddie’s point of view, or William Collyer’s point of view, I still would have done it, because the central theme is interesting. That’s my only criterion, really.

Did you consider approaching The Deep Blue Sea from one of the male characters’ points of view, then?

No. It’s clearly Hester’s point of view, really. In the play, the whole of the first act is exposition. She’s off-stage and Mrs Elton tells you everything. As soon as I knew it was from her point of view, then I knew what to do. Because then you can get rid of all that explanation and exposition, because we see—we actually see—what her memories are. No, it was clear, for me, that I had to do it from Hester’s point of view. And the Rattigan Trust agreed with me – thank god! [Laughs]

I’m always curious to learn how filmmakers approach the matter of dialogue when working from a well-regarded source play. Did you feel obliged to retain Rattigan’s words?

It’s a mixture of cutting down a lot of talk—of people telling you what happens—and a mixture of my own dialogue. We never see Mr Elton, for instance, in the play. We never see William Collyer’s mother. Because if all you’re going to do is photograph the play, it seems to me there’s no point in that. The theatre is a spoken medium. That isn’t true of the cinema. The cinema can show, it can be real. I felt I had to make it cinematic rather than just a collection of people talking, which is not very interesting, really!

What for you is ‘cinematic’?

Cinema tells you what goes on behind the eyes. It absorbs and captures truth in a way that other mediums don’t. It also captures the fleeting moment, when the actor isn’t even aware of it – they’ve just done it. It captures that. But what it does at its best, it reveals rather than shows, rather than illustrates. And it reveals, most importantly, what goes on behind the eyes.

Each of your films has been set in the past and many of these have, by your own admission, been informed by your own memories and experiences.

Yes…

I know I haven’t exactly managed to formulate a question here, but can you talk a little on the way memory informs your filmmaking?

The problem with film is that it’s always in the eternal present; a cut always means that what follows is what happens next. That’s OK, as far as it goes. It’s just that a lot of linear narrative ends up telling you what you should see. Now, I don’t find that interesting. I think it’s much more interesting to be ambiguous, so that the audience can work out the ambiguity that lies between the cuts. My great love is Eliot. When I was 16, on the television over four nights—in 1961, I think—Alec Guinness read from memory the whole of the Four Quartets, which is about the nature of time and memory. I’m just fascinated by the way in which we experience time and memory. As soon as I knew that the play was from Hester’s point of view I knew I could use that within an impressionistic narrative.

Next year you’ll be directing a production of Uncle Vanya for the Wyndham Theatre—

Yes. We’re not sure when that will go ahead because of various commitments that I’ve got and the actors I’m seeing [in consideration for the play] at the moment have got. If we don’t do it this year, then we’ll do it in 2013. But it’s definitely coming off – to my joy! Because I love Chekhov. I love all the Chekhov plays and I love ‘Uncle Vanya’ most.

Am I correct in understanding this will be your first time directing for theatre?

This is my first foray into the theatre. Keep your fingers crossed that I don’t make a pig’s ear of it! [Laughs]

I’m confident we needn’t worry about that! I’m wondering though: what’s intrigued you about the prospect of directing for theatre now, at this point in your career? You’ve already spoken of your love for Chekhov – have you ever considered trying to adapt Chekhov for the screen? Why theatre now?

Oh no, I couldn’t. If you were going to adapt it for the screen, it means rearranging the play, cutting out a lot of dialogue. And because he’s my idol I couldn’t do it. I’d think ‘Oh, he’d be so furious!’ For me, those texts of Anton Chekhov are just sacred. You can’t play around with them. And what you also can’t do is just film them, because they’re not films – they’re plays. They work in a completely different way than cinema. And I couldn’t possibly rearrange it for cinema, I just couldn’t. I would feel that he’d be really angry with me. And quite right too, if you ask me!

Have you ever enjoyed a filmed version of a play? Or as a filmmaker do you find the experience too frustrating?

There are only two exceptions for that, and usually it’s because of performances. The Man Who Came to Dinner in the ’40s with a wonderful central performance by Monty Woolley as Sheridan Whiteside [is one]. And the other is [from] 1952: the Anthony Asquith version of The Importance of Being Earnest. Which is just a photographed play, but has wonderful performances that you really do relish. And you watch it for that. Because it’s not cinematic in the least! [Laughs]

What do you think of this modern practice of live relays of theatrical productions from New York, say, or London, being broadcast into cinemas around the world? Is there any chance we might see one of these for your Uncle Vanya?

Oh, god! Let’s see how it turns out first, I think! Because if, as I said, it’s a pig’s ear, then no one would want it to [be relayed]. And I wouldn’t blame them, would you? [Laughs]

Am I correct in inferring that you feel there are certain works which have found their ideal expression in their original medium? Chekhov, for you, should be constrained to the theatre, because you can’t improve upon [his work] in another medium, and indeed, to tamper with it would be sacrilege. Whereas in the Rattigan play, you’ve seen something which has made you think ‘You know what? I can add something to this. I can play around with this and I don’t feel I’ll be committing unmitigated blasphemy in doing so.’

Yes. I don’t adore Rattigan as I adore Chekhov. He has been called the English Chekhov and I think that’s pitching it a bit high, quite honestly! I suppose because I’m not a huge fan… If I were a huge fan, I’d have been frightened. And I was frightened, initially. [But] the Rattigan Trust—particularly Alan Brodie—just said ‘No, be radical with it.’ So I said ‘Fine, I will be!’ Because you’ve got to find the core of the play and then make that the film. Not just photograph people talking, because, as I say, it’s just not interesting. Cinema is a visual medium. Sound enhances those images. A play is a record of a spoken event. If you just record that, then there’s no point. You might as well go to the theatre and watch it. That’s the place for it. There are people who don’t like what I’ve done. One woman after a Q&A said ‘Why has he ruined a perfectly good play?’

How do you respond to that?

There’s nothing you can say, really. Another woman came out and said ‘I want to blow my brains out.’ So that’s been difficult. But other people come up and say it’s wonderful. It’s six of one and half a dozen of the other, really. It’s not to everybody’s taste, I can assure you!

Before we run out of time, I’d quickly like to ask how you came to choose Rachel Weisz and Tom Hiddleston for their roles, as I think they’re both really splendid in your film.

With Tom Hiddleston I had to audition a lot of people [for the part of Freddie] because it’s not an easy role to do. He just came in halfway through with the passion [required] of that role and it was obvious that he was right. I just knew as soon as we started to do the scenes together. With Rachel Weisz… I don’t go to the cinema very often. I switched the television on, this film was already on [1997’s Swept From the Sea], and I thought ‘This girl is fantastic.’ I watched until the end and it said ‘Rachel Weisz’. I rang my manager and said ‘Have you heard of someone called Rachel Weisz?’ He says ‘Terence, you’re the only one who hasn’t!’ I said ‘Can you send [the script] to her?’ We sent it to her, she read it, she rang me. I said ‘If you say no I have no idea who I’ll approach.’ And she said ‘Can I sleep on it overnight?’ I said ‘Yes, but can you tell me straight away?’ And she said yes! [Laughs]

[[gerard]] Gerard Elson