Josephine Rowe chats with Jessica Au about her short-story collection, Tarcutta Wake

Your stories are sometimes closer to vignettes – a glimpse into a life or a moment. Does preventing the reader from knowing more conversely give a piece greater imaginative depth?

That’s certainly the hope! I often liken it to photography, in that with a good photograph the ideas extend beyond the image – you can ‘see’ beyond the frame. Of course one reader will take different ideas and make different extensions to the next, but that’s the beauty of it. I’ve never really thought of it as being preventative.

On a similar vein, how do you know the point at which a story should end, where you should leave us?

It always depends on the story. Sometimes I know where to end before I’ve any idea on where or how to start. As a reader, I’m skeptical of tidy endings. Graham Greene said it best: ‘A story has no beginning or end: arbitrarily one chooses that moment of experience from which to look back or from which to look ahead.’

In ‘All you really have to do is be here’ (a story about a surrogate mother who’s working as a temporary caretaker of a rural tourist attraction) I chose to end at the moment of threat. I sat with that one for a while. A man walks into a room and…? And nothing. The end. I thought, Can I really get away with that? Is a reader going to feel cheated? Are they going to throw the book across the room? But within the context of the story, there’s an inevitability inherent in that ending; there’s only one direction it can move in from that point – something awful happens. Spelling it out seemed gratuitous.

You have a strong eye for visual detail – dust the ‘[c]olour of dirty goose feathers’, ‘anodised aluminium cups’. How much do you feel writing can turn on objects and a sense of atmosphere?

I thought a lot about relics and the value of objects when I was writing Tarcutta Wake. The early stories in the collection – ‘Suitable for a lampshade’, ‘Brisbane’, ‘Scar from a trick with a knife’ – all dealt with relics in some way or another, in either a tangible or abstract sense, and I decided to run with this theme for the rest of the collection.

So, looking specifically at objects: why is stuff not just stuff? How do things become valuable to us?

I think that an object we’re sentimental about is the abstract made artifact; time, memory, an idea we have of ourselves or somebody else’s feeling for us. A postcard or a letter from a loved one generally holds more sentimental value than, say, an email that contains the same message.

The postcard is something that we can pick up, hold in our hands, something that was held in theirs. (I do realise this sounds hopelessly romantic and nostalgic, which is probably why I’m such a terrible hoarder – I have trouble throwing anything away. Maybe that says something about the spareness of my writing.)

If I write ‘anodised aluminium cups’, what it might say to you as a reader, depending on who you are, is ‘picnics at the beach with my parents’ or ‘those awful things that were everywhere when I was a kid’ or ‘picnicware from an era I didn’t belong to’. In any case, they work as a kind of visual shorthand for ‘something that was that now isn’t’.

‘Suitable for a lampshade’ is a beautiful story of grief, guilt and repair. Take us through the process, how did this piece evolve for you?

‘Suitable for a lampshade’ started with just the title. I was visiting a friend, and she’d just picked up a book about crochet and macramé that she was going to give someone as a birthday present. I flipped through the chapter headings and got to ‘Suitable For a Lampshade’, which I thought was a very beautiful phrase, so I wrote it into my notebook.

Writing is essentially a rag and bone trade – you collect things, not knowing whether they’ll be of value further along. I carried this little scrap of a phrase around for almost a year, and eventually the story sort of accumulated around it. I’ve never been a linear writer – I’d like to be, but I just don’t think that way. I’m tangential. For this story, the process mirrored the setting, in a way – it takes place in a coastal holiday house filled with mismatched, accumulated objects that make sense when viewed as a whole.

You’ve also taken part in the University of Iowa’s International Writing Program (a school which counts John Kinsella and Alice Pung amongst its alumni). What was your time there like?

It was surreal; thirty-seven writers from thirty-five countries split between two hotels, living and working and drinking together for three months – it sounds like a pitch for a reality TV show. Actually I think that some years ago, a Georgian writer wrote a bestseller based on his time at the IWP. I was living in Iowa House, alongside poets from Palestine, Nigeria and the Philippines, a journo from South Africa, fiction writers from Granada, China, Haiti and Venezuela and a playwright from Singapore.

Most of us had projects that kept us in our respective rooms, at our respective desks during the day. I was working on the stories from Tarcutta Wake, looking out my window at squirrels and pines and the Iowa River, and writing about rural NSW and crumbling art deco blocks in St Kilda. But at five o’clock, happy hour would usually coax us out, and our evenings were spent crowded around tables, discussing everything from the death of narrative in American poetry, to untranslatable words and concepts, to the best place to buy fries in Iowa City.

That’s to say nothing of the incredible opportunities that kept falling into our laps, but that was the real meat of it for me – my world view just expanded at those plastic outdoor tables. I came away with very different ideas of fairness and unfairness, spending time with writers who’d been imprisoned numerous times because their work was seen as anti-government. ‘I used to write fiction,’ one of the poets said, ‘but now I write poetry. They don’t know how to read poetry.’

Tell us about the writers or short stories that you’ve loved in the past.

In the past month I’ve read (or re-read) and loved: Carson McCullers’s ‘A Court in the West Eighties’, Ray Bradbury’s ‘The Fog Horn’, Alex Epstein’s ‘A Story in Which No Snow Will Fall’, Junot Diaz’ ‘Ysrael’, Jennifer Mills’s The Rest is Weight, and excerpts from Tara June Winch’s Swallow the Air, which is a novel comprised of beautiful, self-contained stories.

Jayne Anne Phillips’s ‘Black Tickets’ is a collection that I go back to again and again – my brother-in-law leant it to me when I was eighteen or nineteen, and I fell for it hard.

I’m a big fan of Alistair MacLeod’s stories. I’ve read few writers who capture place so beautifully. His stories are mostly situated in Atlantic Canada, where my husband is from, so I’ve spent a little time there, staying in little fishing communities that are Alistair MacLeod stories.

Richard Brautigan I pick up whenever I’m feeling despondent. ‘Pacific Radio Fire’ is my all time favourite. There are two camps on Brautigan: those who love him, and those who dismiss him as not being a ‘serious writer’. I’m definitely in the first camp – he instills everyday words with a kind of sad and beautiful magic.

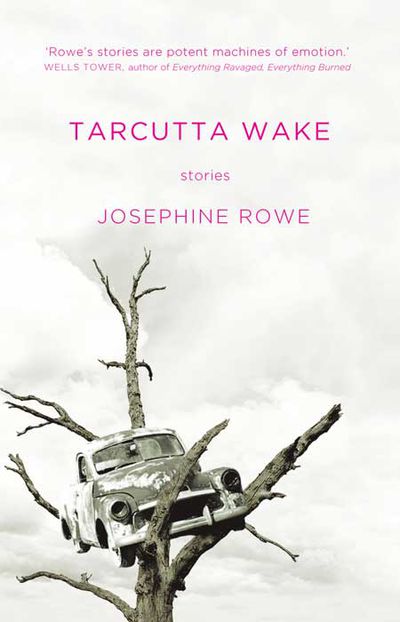

Tarcutta Wake