Readings Newsletter

Become a Readings Member to make your shopping experience even easier.

Sign in or sign up for free!

You’re not far away from qualifying for FREE standard shipping within Australia

You’ve qualified for FREE standard shipping within Australia

The cart is loading…

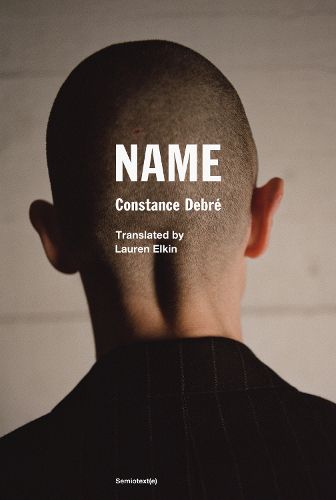

A searing disavowal of identity and inheritance, which completes Constace Debre's acclaimed trilogy.

I have a political agenda. I am in favor of the elimination of inheritance, the requirement that ancestors sustain their descendants, I am for the elimination of parental authority, I am for the abolition of marriage, I am in favor of children getting some distance from their parents at as young an age as possible, I am for the abolition of filiation, and for the abolition of the family name, I am against guardianship, minority, I am against patrimony, I am against having a domicile, a nationality ... I am for eliminating the family, I am in favor of eliminating childhood as well, if we can.

Name, the third novel in Constance Debre's acclaimed trilogy, is at once a manifesto, an ecstatic poem, and a political pamphlet. By rejecting the notion of given identity, her narrator approaches the heart of the radical emptiness that the earlier books were pursuing.

Newly single, and having recently come out as a lesbian, the narrator of Debre's first two novels embarked on a monastic regime of exercise, sex, and writing. Using the facts of her own life as impersonal "material" for literature, Playboy and Love Me Tender epitomized what Debre (after Thomas Bernhard) has called "antiautobiography." They introduced French and American readers to her fiercely spare prose, distilled from influences as disparate as Saint Augustine, Albert Camus, and Guillaume Dustan. "Minimalist and at times even desolate," wrote the New York Review of Books, these works defied "the expectations of personal growth that animate much feminist literature."

Name is Debre's most intense novel yet. Set partly in the narrator's childhood, it rejects Proustian notions of "regaining" the past. Instead, its narrator seeks a state of profound disownment: "We have to get rid of the idea of origins, once and for all, I'm not holding onto the corpses. ... Being free has nothing to do with that clutter, with having suffered or not, being free is the void." To achieve true freedom, she dares to enter this "void"-that is, dares to accept the pain, loss, and violence of life. Brilliant and searing, Name affirms and extends Debre's radical project.

$9.00 standard shipping within Australia

FREE standard shipping within Australia for orders over $100.00

Express & International shipping calculated at checkout

A searing disavowal of identity and inheritance, which completes Constace Debre's acclaimed trilogy.

I have a political agenda. I am in favor of the elimination of inheritance, the requirement that ancestors sustain their descendants, I am for the elimination of parental authority, I am for the abolition of marriage, I am in favor of children getting some distance from their parents at as young an age as possible, I am for the abolition of filiation, and for the abolition of the family name, I am against guardianship, minority, I am against patrimony, I am against having a domicile, a nationality ... I am for eliminating the family, I am in favor of eliminating childhood as well, if we can.

Name, the third novel in Constance Debre's acclaimed trilogy, is at once a manifesto, an ecstatic poem, and a political pamphlet. By rejecting the notion of given identity, her narrator approaches the heart of the radical emptiness that the earlier books were pursuing.

Newly single, and having recently come out as a lesbian, the narrator of Debre's first two novels embarked on a monastic regime of exercise, sex, and writing. Using the facts of her own life as impersonal "material" for literature, Playboy and Love Me Tender epitomized what Debre (after Thomas Bernhard) has called "antiautobiography." They introduced French and American readers to her fiercely spare prose, distilled from influences as disparate as Saint Augustine, Albert Camus, and Guillaume Dustan. "Minimalist and at times even desolate," wrote the New York Review of Books, these works defied "the expectations of personal growth that animate much feminist literature."

Name is Debre's most intense novel yet. Set partly in the narrator's childhood, it rejects Proustian notions of "regaining" the past. Instead, its narrator seeks a state of profound disownment: "We have to get rid of the idea of origins, once and for all, I'm not holding onto the corpses. ... Being free has nothing to do with that clutter, with having suffered or not, being free is the void." To achieve true freedom, she dares to enter this "void"-that is, dares to accept the pain, loss, and violence of life. Brilliant and searing, Name affirms and extends Debre's radical project.