Readings Newsletter

Become a Readings Member to make your shopping experience even easier.

Sign in or sign up for free!

You’re not far away from qualifying for FREE standard shipping within Australia

You’ve qualified for FREE standard shipping within Australia

The cart is loading…

This title is printed to order. This book may have been self-published. If so, we cannot guarantee the quality of the content. In the main most books will have gone through the editing process however some may not. We therefore suggest that you be aware of this before ordering this book. If in doubt check either the author or publisher’s details as we are unable to accept any returns unless they are faulty. Please contact us if you have any questions.

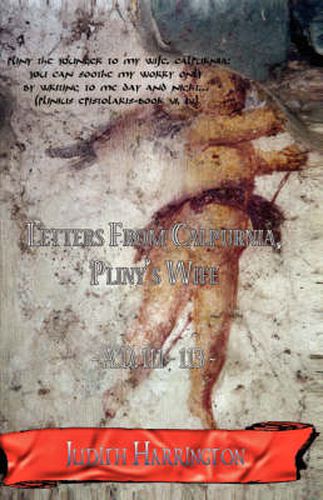

During a Fulbright year (1993-94) in Turkey, I discovered these letters while working in the library of the Christian shrine, Meryamana Evi, located in the mountains above the ruins of Ephesus. Written in Latin and Greek on vellum and papyrus, they were apparently composed by a Roman matron named Calpurnia to her husband, Gaius Plinius, whom she also addresses as Caecilius and Lucius. According to tradition, the shrine of Meryamana Evi is the ancient heart of the Johannine Community whose members composed the Gospel of St. John; it is recognized by Roman Catholics as the location of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary into Heaven. I found the manuscript among a jumble of archaeological documents, votives left by cured pilgrims, and religious relics donated for decades by Christian and Muslim visitors from all over the world. I traced the manuscript to an ancient papyrus dump discovered by Grenfel and Hunt in the 1890’s near ‘Behneseh’ at Oxyrhynchus, Egypt, 300 kilometers south of Alexandria. During the last decade, I have been trying to authenticate my discovery. My attempts were complicated by tragic circumstances of the 1999 earthquake in northwestern Turkey that resulted in the disappearance of the original manuscript; to protect it, I have copyrighted my translation under the title Letters from Calpurnia, Pliny’s Wife. This collection, with the letters organized into eight books and an epilogue, is as sequential as I have been able to determine. The selected, annotated bibliography reflects sources I have used in my research. Links to the bibliographic sources may be found on the website indicated in the bibliography. I am currently compiling additional letters for a second volume, with commentary by my friend and colleague, Dr. Arthur Saunier. Apparently, Calpurnia wrote most of the letters* I include here to her husband Pliny the Younger, from Ephesus between 111-113 A.D. while he was Emperor Trajan’s legatus in Bithynia, a Roman province in what is now northwestern Turkey. It was from there that Pliny wrote his famous letter to Trajan about the behavior and fate of local Christians. Having studied the letters of Calpurnia side by side with her husband’s published letters, I now read Pliny’s epistle to Trajan as a frantic plea, couched in legitimate Roman terms, for the safety of innocent members of the new Christian cult, which included his wife. In her letters, Calpurnia tells Gaius about her fascination with this new religious cult, whose god she feels holds the best hope of curing the infertility she has suffered since a miscarriage during the first year of their marriage. It appears that Gaius, in an effort to distract Calpurnia from this risky mission and to keep her mind occupied, asks his wife to send him mundane information like recipes and remedies (which I would caution against trying), notations and lyrics for the music she composes on the kithyra, and her opinions about Roman religion and politics. Gaius also arranges to send her manuscripts from the extensive library of his Uncle Pliny the Elder, together with those he discovers in a network of libraries during his travels throughout the eastern provinces of the Roman Empire, telling her to translate parts of them from the original into either Latin or Greek. Calpurnia obediently sends Gaius her translated summaries of bits and pieces of works as diverse as Asclepius’s Treatice on Dreams and Soranus’s Gynecology. She explains her midwife experience with Soranus, whom she has met at Ephesus, and describes the snake treatment she takes for her infertility at the Asclepion center of healing at Pergamum. Included in her letters are prescriptions for anthrax and other diseases. She also expresses anxiety about the behavior of her young artist protege, the genius Stephanos (whose artist ancestor, Stephanus, is mentioned in Book XXXVI of Pliny the Elder’s Natural History), and worries about what to do with the blood-stained Shrou

$9.00 standard shipping within Australia

FREE standard shipping within Australia for orders over $100.00

Express & International shipping calculated at checkout

This title is printed to order. This book may have been self-published. If so, we cannot guarantee the quality of the content. In the main most books will have gone through the editing process however some may not. We therefore suggest that you be aware of this before ordering this book. If in doubt check either the author or publisher’s details as we are unable to accept any returns unless they are faulty. Please contact us if you have any questions.

During a Fulbright year (1993-94) in Turkey, I discovered these letters while working in the library of the Christian shrine, Meryamana Evi, located in the mountains above the ruins of Ephesus. Written in Latin and Greek on vellum and papyrus, they were apparently composed by a Roman matron named Calpurnia to her husband, Gaius Plinius, whom she also addresses as Caecilius and Lucius. According to tradition, the shrine of Meryamana Evi is the ancient heart of the Johannine Community whose members composed the Gospel of St. John; it is recognized by Roman Catholics as the location of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary into Heaven. I found the manuscript among a jumble of archaeological documents, votives left by cured pilgrims, and religious relics donated for decades by Christian and Muslim visitors from all over the world. I traced the manuscript to an ancient papyrus dump discovered by Grenfel and Hunt in the 1890’s near ‘Behneseh’ at Oxyrhynchus, Egypt, 300 kilometers south of Alexandria. During the last decade, I have been trying to authenticate my discovery. My attempts were complicated by tragic circumstances of the 1999 earthquake in northwestern Turkey that resulted in the disappearance of the original manuscript; to protect it, I have copyrighted my translation under the title Letters from Calpurnia, Pliny’s Wife. This collection, with the letters organized into eight books and an epilogue, is as sequential as I have been able to determine. The selected, annotated bibliography reflects sources I have used in my research. Links to the bibliographic sources may be found on the website indicated in the bibliography. I am currently compiling additional letters for a second volume, with commentary by my friend and colleague, Dr. Arthur Saunier. Apparently, Calpurnia wrote most of the letters* I include here to her husband Pliny the Younger, from Ephesus between 111-113 A.D. while he was Emperor Trajan’s legatus in Bithynia, a Roman province in what is now northwestern Turkey. It was from there that Pliny wrote his famous letter to Trajan about the behavior and fate of local Christians. Having studied the letters of Calpurnia side by side with her husband’s published letters, I now read Pliny’s epistle to Trajan as a frantic plea, couched in legitimate Roman terms, for the safety of innocent members of the new Christian cult, which included his wife. In her letters, Calpurnia tells Gaius about her fascination with this new religious cult, whose god she feels holds the best hope of curing the infertility she has suffered since a miscarriage during the first year of their marriage. It appears that Gaius, in an effort to distract Calpurnia from this risky mission and to keep her mind occupied, asks his wife to send him mundane information like recipes and remedies (which I would caution against trying), notations and lyrics for the music she composes on the kithyra, and her opinions about Roman religion and politics. Gaius also arranges to send her manuscripts from the extensive library of his Uncle Pliny the Elder, together with those he discovers in a network of libraries during his travels throughout the eastern provinces of the Roman Empire, telling her to translate parts of them from the original into either Latin or Greek. Calpurnia obediently sends Gaius her translated summaries of bits and pieces of works as diverse as Asclepius’s Treatice on Dreams and Soranus’s Gynecology. She explains her midwife experience with Soranus, whom she has met at Ephesus, and describes the snake treatment she takes for her infertility at the Asclepion center of healing at Pergamum. Included in her letters are prescriptions for anthrax and other diseases. She also expresses anxiety about the behavior of her young artist protege, the genius Stephanos (whose artist ancestor, Stephanus, is mentioned in Book XXXVI of Pliny the Elder’s Natural History), and worries about what to do with the blood-stained Shrou