Readings Newsletter

Become a Readings Member to make your shopping experience even easier.

Sign in or sign up for free!

You’re not far away from qualifying for FREE standard shipping within Australia

You’ve qualified for FREE standard shipping within Australia

The cart is loading…

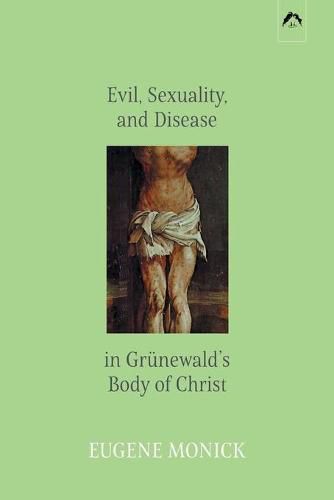

This wonderfully readable work by the Jungian analyst Eugene Monick is about an equally wondrous, if difficult, artwork. Grunewald’s famous Isenheim altarpiece, now located at Colmar in the Alsatian part of France, contains a strange and troubling image: a portrayal of Jesus’s body, skin yellowed and greened, covered with pus and scabs, thoroughly diseased. This image - what archetypal psychologists Rafael Lopez-Pedraza, Niel Micklem, and Alfred Ziegler, following the poet Jose Lezama Lima, have called an intolerable image - constitutes both the wondrous and difficult dimensions of Monick’s theme. Surprising as it may seem with so distressing a topic, and like the Isenheim altarpiece itself, this book offers relief, a welcome remedy to incessant blame, as Monick himself puts it, an antidote to the huge and fruitless effort of seeking a perfect and stainless way. The fascination, then, is in seeing how a blemished image of Jesus paradoxically constitutes precisely a Christic sense of self without blemish. (David L. Miller)

$9.00 standard shipping within Australia

FREE standard shipping within Australia for orders over $100.00

Express & International shipping calculated at checkout

This wonderfully readable work by the Jungian analyst Eugene Monick is about an equally wondrous, if difficult, artwork. Grunewald’s famous Isenheim altarpiece, now located at Colmar in the Alsatian part of France, contains a strange and troubling image: a portrayal of Jesus’s body, skin yellowed and greened, covered with pus and scabs, thoroughly diseased. This image - what archetypal psychologists Rafael Lopez-Pedraza, Niel Micklem, and Alfred Ziegler, following the poet Jose Lezama Lima, have called an intolerable image - constitutes both the wondrous and difficult dimensions of Monick’s theme. Surprising as it may seem with so distressing a topic, and like the Isenheim altarpiece itself, this book offers relief, a welcome remedy to incessant blame, as Monick himself puts it, an antidote to the huge and fruitless effort of seeking a perfect and stainless way. The fascination, then, is in seeing how a blemished image of Jesus paradoxically constitutes precisely a Christic sense of self without blemish. (David L. Miller)