Readings Newsletter

Become a Readings Member to make your shopping experience even easier.

Sign in or sign up for free!

You’re not far away from qualifying for FREE standard shipping within Australia

You’ve qualified for FREE standard shipping within Australia

The cart is loading…

This title is printed to order. This book may have been self-published. If so, we cannot guarantee the quality of the content. In the main most books will have gone through the editing process however some may not. We therefore suggest that you be aware of this before ordering this book. If in doubt check either the author or publisher’s details as we are unable to accept any returns unless they are faulty. Please contact us if you have any questions.

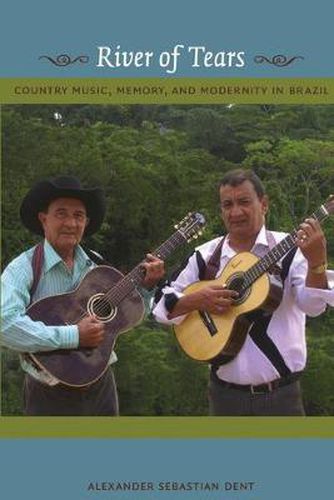

River of Tears is the first ethnography of Brazilian country music, one of the most popular genres in Brazil yet least-known outside it. Beginning in the mid-1980s, commercial musical duos practicing musica sertaneja reached beyond their home in Brazil’s central-southern region to become national bestsellers. Rodeo events revolving around country music came to rival soccer matches in attendance. A revival of folkloric rural music called musica caipira, heralded as musica sertaneja’s ancestor, also took shape. And all the while, large numbers of Brazilians in the central-south were moving to cities, using music to support the claim that their Brazil was first and foremost a rural nation.Since 1998, Alexander Sebastian Dent has analyzed rural music in the state of Sao Paulo, interviewing and spending time with listeners, musicians, songwriters, journalists, record-company owners, and radio hosts. Dent not only describes the production and reception of this music, he also explains why the genre experienced such tremendous growth as Brazil transitioned from an era of dictatorship to a period of intense neoliberal reform. Dent argues that rural genres reflect a widespread anxiety that change has been too radical and has come too fast. In defining their music as rural, Brazil’s country musicians-whose work circulates largely in cities-are criticizing an increasingly inescapable urban life characterized by suppressed emotions and an inattentiveness to the past. Their performances evoke a river of tears flowing through a landscape of loss-of love, of life in the countryside, and of man’s connections to the natural world.

$9.00 standard shipping within Australia

FREE standard shipping within Australia for orders over $100.00

Express & International shipping calculated at checkout

This title is printed to order. This book may have been self-published. If so, we cannot guarantee the quality of the content. In the main most books will have gone through the editing process however some may not. We therefore suggest that you be aware of this before ordering this book. If in doubt check either the author or publisher’s details as we are unable to accept any returns unless they are faulty. Please contact us if you have any questions.

River of Tears is the first ethnography of Brazilian country music, one of the most popular genres in Brazil yet least-known outside it. Beginning in the mid-1980s, commercial musical duos practicing musica sertaneja reached beyond their home in Brazil’s central-southern region to become national bestsellers. Rodeo events revolving around country music came to rival soccer matches in attendance. A revival of folkloric rural music called musica caipira, heralded as musica sertaneja’s ancestor, also took shape. And all the while, large numbers of Brazilians in the central-south were moving to cities, using music to support the claim that their Brazil was first and foremost a rural nation.Since 1998, Alexander Sebastian Dent has analyzed rural music in the state of Sao Paulo, interviewing and spending time with listeners, musicians, songwriters, journalists, record-company owners, and radio hosts. Dent not only describes the production and reception of this music, he also explains why the genre experienced such tremendous growth as Brazil transitioned from an era of dictatorship to a period of intense neoliberal reform. Dent argues that rural genres reflect a widespread anxiety that change has been too radical and has come too fast. In defining their music as rural, Brazil’s country musicians-whose work circulates largely in cities-are criticizing an increasingly inescapable urban life characterized by suppressed emotions and an inattentiveness to the past. Their performances evoke a river of tears flowing through a landscape of loss-of love, of life in the countryside, and of man’s connections to the natural world.