Readings Newsletter

Become a Readings Member to make your shopping experience even easier.

Sign in or sign up for free!

You’re not far away from qualifying for FREE standard shipping within Australia

You’ve qualified for FREE standard shipping within Australia

The cart is loading…

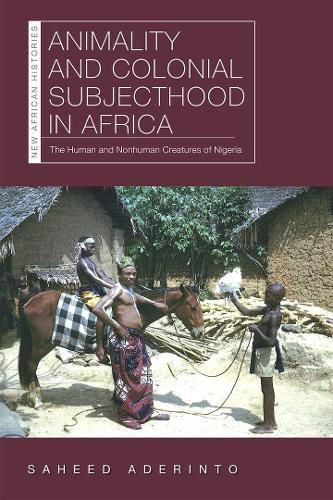

With this multispecies study of animals as instrumentalities of the colonial state in Nigeria, Saheed Aderinto argues that animals, like humans, were colonial subjects in Africa.

Animality and Colonial Subjecthood in Africa broadens the historiography of animal studies by putting a diverse array of species (dogs, horses, livestock, and wildlife) into a single analytical framework for understanding colonialism in Nigeria and Africa as a whole.

From his study of animals with unequal political, economic, social, and intellectual capabilities, Aderinto establishes that the core dichotomies of human colonial subjecthood–indispensable yet disposable, good and bad, violent but peaceful, saintly and lawless–were also embedded in the identities of Nigeria’s animal inhabitants. If class, religion, ethnicity, location, and attitude toward imperialism determined the pattern of relations between human Nigerians and the colonial government, then species, habitat, material value, threat, and biological and psychological characteristics (among other traits) shaped imperial perspectives on animal Nigerians.

Conceptually sophisticated and intellectually engaging, Aderinto’s thesis challenges readers to rethink what constitutes history and to recognize that human agency and narrative are not the only makers of the past.

$9.00 standard shipping within Australia

FREE standard shipping within Australia for orders over $100.00

Express & International shipping calculated at checkout

With this multispecies study of animals as instrumentalities of the colonial state in Nigeria, Saheed Aderinto argues that animals, like humans, were colonial subjects in Africa.

Animality and Colonial Subjecthood in Africa broadens the historiography of animal studies by putting a diverse array of species (dogs, horses, livestock, and wildlife) into a single analytical framework for understanding colonialism in Nigeria and Africa as a whole.

From his study of animals with unequal political, economic, social, and intellectual capabilities, Aderinto establishes that the core dichotomies of human colonial subjecthood–indispensable yet disposable, good and bad, violent but peaceful, saintly and lawless–were also embedded in the identities of Nigeria’s animal inhabitants. If class, religion, ethnicity, location, and attitude toward imperialism determined the pattern of relations between human Nigerians and the colonial government, then species, habitat, material value, threat, and biological and psychological characteristics (among other traits) shaped imperial perspectives on animal Nigerians.

Conceptually sophisticated and intellectually engaging, Aderinto’s thesis challenges readers to rethink what constitutes history and to recognize that human agency and narrative are not the only makers of the past.