Readings Newsletter

Become a Readings Member to make your shopping experience even easier.

Sign in or sign up for free!

You’re not far away from qualifying for FREE standard shipping within Australia

You’ve qualified for FREE standard shipping within Australia

The cart is loading…

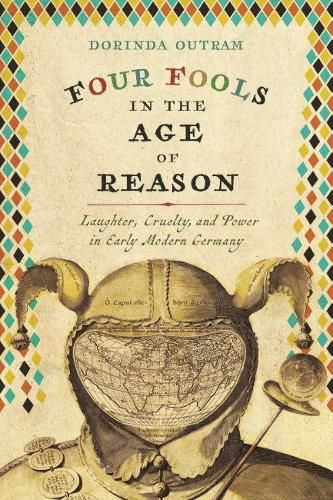

Unveiling the nearly lost world of the court fools of eighteenth-century Germany, Dorinda Outram shows that laughter was an essential instrument of power. Whether jovial or cruel, mirth altered social and political relations.

Outram takes us first to the court of Frederick William I of Prussia, who emerges not only as an administrative reformer and notorious militarist but also as a

master of fools,

a ruler who used fools to prop up his uncertain power. The autobiography of the itinerant fool Peter Prosch affords a rare insider’s view of the small courts in Catholic south Germany, Austria, and Bavaria. Full of sharp observations of prelates and princes, the autobiography also records episodes of the extraordinary cruelty for which the German princely courts were notorious. Joseph Froehlich, court fool in Dresden, presents more appealing facets of foolery. A sharp salesman and hero of the Meissen factories, he was deeply attached to the folk life of fooling. The book ends by tying the growth of Enlightenment skepticism to the demise of court foolery around 1800.

Outram’s book is invaluable for giving us such a vivid depiction of the court fool and especially for revealing how this figure can shed new light on the wielding of power in Enlightenment Europe.

$9.00 standard shipping within Australia

FREE standard shipping within Australia for orders over $100.00

Express & International shipping calculated at checkout

Unveiling the nearly lost world of the court fools of eighteenth-century Germany, Dorinda Outram shows that laughter was an essential instrument of power. Whether jovial or cruel, mirth altered social and political relations.

Outram takes us first to the court of Frederick William I of Prussia, who emerges not only as an administrative reformer and notorious militarist but also as a

master of fools,

a ruler who used fools to prop up his uncertain power. The autobiography of the itinerant fool Peter Prosch affords a rare insider’s view of the small courts in Catholic south Germany, Austria, and Bavaria. Full of sharp observations of prelates and princes, the autobiography also records episodes of the extraordinary cruelty for which the German princely courts were notorious. Joseph Froehlich, court fool in Dresden, presents more appealing facets of foolery. A sharp salesman and hero of the Meissen factories, he was deeply attached to the folk life of fooling. The book ends by tying the growth of Enlightenment skepticism to the demise of court foolery around 1800.

Outram’s book is invaluable for giving us such a vivid depiction of the court fool and especially for revealing how this figure can shed new light on the wielding of power in Enlightenment Europe.