Readings Newsletter

Become a Readings Member to make your shopping experience even easier.

Sign in or sign up for free!

You’re not far away from qualifying for FREE standard shipping within Australia

You’ve qualified for FREE standard shipping within Australia

The cart is loading…

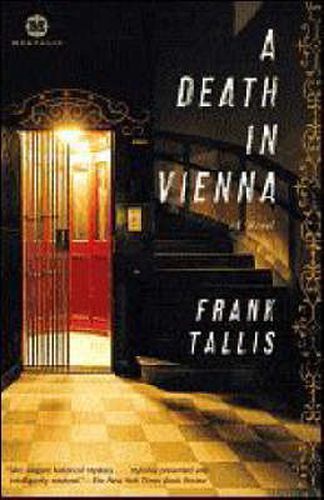

In 1902, elegant Vienna is the city of the new century, the center of discoveries in everything from the writing of music to the workings of the human mind. But now a brutal homicide has stunned its citizens and appears to have bridged the gap between science and the supernatural. Two very different sleuths from opposite ends of the spectrum will need to combine their talents to solve the boggling crime: Detective Oskar Rheinhardt, who is on the cutting edge of modern police work, and his friend Dr. Max Liebermann, a follower of Sigmund Freud and a pioneer on new frontiers of psychology. As a team they must use both hard evidence and intuitive analysis to solve a medium’s mysterious murder-one that couldn’t have been committed by anyone alive. __________________________________________________________ THE MORTALIS DOSSIER- PSYCHOLOGICAL THRILLERS: THE CURIOUS CASE OF PROFESSOR SIGMUND F. AND DETECTIVE FICTION Summertime-the Austrian Alps: A middle-aged doctor, wishingto forget medicine, turns off the beaten track and begins a strenuousclimb. When he reaches the summit, he sits and contemplates the distantprospect. Suddenly he hears a voice. Are you a doctor? He is not alone. At first, he can’t believe that he’s being addressed.He turns and sees a sulky-looking eighteen-year-old. He recognizesher (she served him his meal the previous evening). Yes, he replies. I’m a doctor. How did you know that? She tells him that her nerves are bad, that she needs help.S ometimes she feels like she can’t breathe, and there’s a hammering inher head. And sometimes something very disturbing happens. She seesthings-including a face that fills her with horror… .Well, do you want to know what happens next? I’d be surprised ifyou didn’t.We have here all the ingredients of an engaging thriller: an isolatedsetting, a strange meeting, and a disconcerting confession.So where does this particular opening scene come from? A littleknownwork by one of the queens of crime fiction? A lost reel of anearly Hitchcock film, perhaps? Neither. It is in fact a faithful summaryof the first few pages of Katharina by Sigmund Freud, also known ascase study number four in his Studies on Hysteria, co-authored with JosefBreuer and published in 1895.It is generally agreed that the detective thriller is a nineteenthcenturyinvention, perfected by the holy trinity of Collins, Poe, and(most importantly) Conan Doyle; however, the genre would havebeen quite different had it not been for the oblique influence of psychoanalysis.The psychological thriller often pays close attention topersonal history-childhood experiences, relationships, and significantlife events-in fact, the very same things that any self-respectingtherapist would want to know about. These days it’s almost impossibleto think of the term thriller without mentally inserting the prefix psychological. So how did this happen? How did Freud’s work come to influencethe development of an entire literary genre? The answer is quite simple.He had some help-and that help came from the American filmindustry.Now it has to be said that Freud didn’t like America. After visitingAmerica, he wrote: I am very glad I am away from it, and even morethat I don’t have to live there. He believed that American food hadgiven him a gastrointestinal illness, and that his short stay in Americahad caused his handwriting to deteriorate. His anti-American sentimentsfinally culminated with his famous remark that he consideredAmerica to be a gigantic mistake. Be that as it may, although Freud didn’t like America, Americaliked Freud. In fact, America loved him. And nowhere in America wasFreud more loved than in Hollywood.The special relationship between the film industry and psychoanalysisbegan in the 1930s, when many EmigrE analysts-fleeingfrom the Nazis-settled on the West Coast. Entering analysis becamevery fashionable among the studio elite, and Hollywood soonacquired the sobriquet couch canyon. Dr. Ralph Greenson, forexample-a well-known Hollywood analyst-had a patient list thatincluded the likes of Marilyn Monroe, Frank Sinatra, Tony Curtis, and Vivien Leigh. And among the many Hollywood directors whosuccumbed to Freud’s influence was Alfred Hitchcock, whose thrillerswere much more psychological than any that had been filmed before.In one of his films Freud actually makes an appearance-well, more orless. I am thinking here of Spellbound, released in 1945, and based onFrancis Beedings’s crime novel The House of Dr. Edwardes. T he producer of Spellbound, David O. Selznick, was himself inpsychoanalysis-as were most of his family-and so enthusiastic washe about Freud’s ideas that he recruited his own analyst to help himvet the script. Hitchcock’s film has everything we expect from a psychologicalthriller: a clinical setting, a murder, a man who has lost hismemory, a dream sequence, and a sinewy plot that twists and turnstoward a dramatic climax. That this film owes a large debt to psychoanalysisis made absolutely clear when a character appears who is-inall but name-Sigmund Freud: a wise old doctor with a beard, glasses, and a fantastically hammy Viennese accent.Since Hitchcock’s time, authors and screenwriters have had muchfun playing with the resonances that exist between psychoanalysis anddetection. This kind of writing reached its apotheosis in 1975 with thepublication of Nicholas Meyer’s The Seven-Per-Cent Solution, a novel inwhich Freud and Sherlock Holmes are brought together to solve thesame case.The relationship between psychoanalysis and detection was notlost on Freud. In his Introductory Lectures, for example, there is a passagein which he stresses how both the detective and the psychoanalyst dependon accumulating piecemeal evidence that usually arrives in theform of small and apparently inconsequential clues. If you were a detective engaged in tracing a murder, would you expect to find that the murderer had left his photograph behind at the place of the crime, with his address attached? Or would you not necessarily have to be satisfied with comparatively slight and obscure traces of the person you were in search of? So do not let us underestimate small indications; by their help we may succeed in getting on the track of somethingbigger. Later in the same series of lectures, Freud blurs the boundary betweenpsychoanalysis and detection even further. He goes beyond pointingout that psychoanalysis and detection are similar enterprises and suggeststhat psychoanalytic techniques might actually be used to aid detection.Freud describes the case of a real murderer who acquired highlydangerous pathogenic organisms from scientific institutes by pretendingto be a bacteriologist. The murderer then used these stolen culturesto fatally infect his victims. On one occasion, he audaciously wrote aletter to the director of one of these scientific institutes, complainingthat the cultures he had been given were ineffective. But the lettercontained a Freudian slip-an unconsciously performed blunder.Instead of writing in my experiments on mice or guinea pigs, the murdererwrote in my experiments on men. Freud notes that the institute director-not being conversant with psychoanalysis-was happy to overlooksuch a telling error.In a little-known paper called Psychoanalysis and the Ascertaining ofTruth in Courts of Law, Freud is even more confident that psychoanalytictechniques might be used in the service of detection. He writes: In both [psychoanalysis and law] we are concerned with asecret, with something hidden… . In the case of the criminal itis a secret which he knows he hides from you, but in the case ofthe hysteric it is a secret hidden from himself… . The task ofthe therapeutist is, however, the same as the task of the judge;he must discover the hidden psychic material. To do this wehave invented various methods of detection, some of whichlawyers are now going to imitate.It is interesting that criminology and forensic science emerged at exactlythe same time as psychoanalysis. In 1893, Professor Hans Gross(also Viennese) published the first handbook of criminal investigation, a manual for detectives. It was the same year that Freud published(with Josef Breuer) his first work on psychoanalysis: a PreliminaryCommunication,

On the Psychical Mechanism of Hysterical Phenomena. Freud, largely via Hollywood, wielded an extraordinary influenceon detective fiction. But to what extent is the reverse true?We know that Freud was very widely read-and that he hadand Vivien Leigh. And among the many Hollywood directors whosuccumbed to Freud’s influence was Alfred Hitchcock, whose thrillerswere much more psychological than any that had been filmed before.In one of his films Freud actually makes an appearance-well, more orless. I am thinking here of Spellbound, released in 1945, and based onFrancis Beedings’s crime novel The House of Dr. Edwardes. The producer of Spellbound, David O. Selznick, was himself inpsychoanalysis-as were most of his family-and so enthusiastic washe about Freud’s ideas that he recruited his own analyst to help himvet the script. Hitchcock’s film has everything we expect from a psychologicalthriller: a clinical setting, a murder, a man who has lost hismemory, a dream sequence, and a sinewy plot that twists and turnstoward a dramatic climax. That this film owes a large debt to psychoanalysisis made absolutely clear when a character appears who is-inall but name-Sigmund Freud: a wise old doctor with a beard, glasses, and a fantastically hammy Viennese accent.Since Hitchcock’s time, authors and screenwriters have had muchfun playing with the resonances that exist between psychoanalysis anddetection. This kind of writing reached its apotheosis in 1975 with thepublication of Nicholas Meyer’s The Seven-Per-Cent Solution, a novel inwhich Freud and Sherlock Holmes are brought together to solve thesame case.The relationship between psychoanalysis and detection was notlost on Freud. In his Introductory Lectures, for example, there is a passagein which he stresses how both the detective and the psychoanalyst dependon accumulating piecemeal evidence that usually arrives in theform of small and apparently inconsequential clues.If you were a detective engaged in tracing a murder, wouldyou expect to find that the murderer had left his photographbehind at the place of the crime, with his address attached? Orwould you not necessarily have to be satisfied with comparativelyslight and obscure traces of the person you were insearch of? So do not let us underestimate small indications; bytheir help we may succeed in getting on the track of somethingbigger.Later in the same series of lectures, Freud blurs the boundary betweenpsychoanalysis and detection even further. He goes beyond pointingout that psychoanalysis and detection are similar enterprises and suggeststhat psychoanalytic techniques might actually be used to aid detection.Freud describes the case of a real murderer who acquired highlydangerous pathogenic organisms from scientific institutes by pretendingto be a bacteriologist. The murderer then used these stolen culturesto fatally infect his victims. On one occasion, he audaciously wrote aletter to the director of one of these scientific institutes, complainingthat the cultures he had been given were ineffective. But the lettercontained a Freudian slip-an unconsciously performed blunder.Instead of writing in my experiments on mice or guinea pigs, the murdererwrote in my experiments on men. Freud notes that the institute director-not being conversant with psychoanalysis- was happy to overlooksuch a telling error.In a little-known paper called Psychoanalysis and the Ascertaining ofTruth in Courts of Law, Freud is even more confident that psychoanalytictechniques might be used in the service of detection. He writes: In both [psychoanalysis and law] we are concerned with asecret, with something hidden… . In the case of the criminal itis a secret which he knows he hides from you, but in the case ofthe hysteric it is a secret hidden from himself… . The task ofthe therapeutist is, however, the same as the task of the judge;he must discover the hidden psychic material. To do this wehave invented various methods of detection, some of whichlawyers are now going to imitate.It is interesting that criminology and forensic science emerged at exactlythe same time as psychoanalysis. In 1893, Professor Hans Gross(also Viennese) published the first handbook of criminal investigation, a manual for detectives. It was the same year that Freud published(with Josef Breuer) his first work on psychoanalysis: a PreliminaryCommunication,

On the Psychical Mechanism of Hysterical Phenomena. Freud, largely via Hollywood, wielded an extraordinary influenceon detective fiction. But to what extent is the reverse true?We know that Freud was very widely read-and that he hadlished a memoir in 1971, which contains a very interesting aside. Thetwo men had been discussing literature, and Freud had expressed hisadmiration for several writers, most of them acknowledged mastersand writers of the first magnitude, such as Dostoevsky. However, bythe Wolfman’s reckoning at least, a lesser talent seemed to have gatecrashedFreud’s literary pantheon.Once we happened to speak of Conan Doyle and his creation, Sherlock Holmes. I had thought that Freud would haveno use for this type of light reading matter, and was surprised tofind that this was not at all the case and that Freud had readthis author attentively. The fact that circumstantial evidenceis useful in psychoanalysis when reconstructing a childhoodhistory may explain Freud’s interest in this type of literature.The Wolfman’s final observation is clearly correct. Crimes are likesymptoms, and the psychoanalyst and detective are similar creatures.Both scrutinize circumstantial evidence, both reconstruct histories, and both seek to establish an ultimate cause.If we broaden our definition of what might legitimately be calleddetective fiction and permit ourselves to consider works written evenbefore Hoffmann’ s Mademoiselle de ScudEry, then we encounter a storythat, without doubt, exerted a profound influence on Freud and thedevelopment of psychoanalysis. It is a story that British writer ChristopherBooker has called the greatest whodunit in all literature. It isone of the earliest stories of murder and detection ever recorded andhas a twist in the tale that still has the power to shock: Oedipus Rex bySophocles.When we meet Oedipus, there is a curse on his country. He is toldthat this curse will not be lifted until he has discovered the identity ofthe man who murdered his predecessor: King Laius, the former husband of Oedipus’s new wife, Jocasta. Oedipus follows clue after clue until his investigation leads him inexorably to a terrible conclusion.It was he, Oedipus, who killed the king. Laius was his father andOedipus is now married to his own mother.This classic tragedy is also an ancient detective story and gave itsname to the cornerstone of psychoanalytic theory-the much mooted(and even more misunderstood) Oedipus complex-a group of largelyunconscious ideas and feelings concerning wishes to possess the parentof the opposite sex and eliminate the parent of the same sex.I think there is something very satisfying about the relationshipbetween psychoanalysis and detective fiction. Freud influenced thecourse of detective fiction, but by the same token, detective fiction (inits broadest possible sense) also influenced Freud. And at a deeperlevel, psychoanalysis-a process that resembles detective work-discovers a whodunit buried in the depths of every human psyche.

$9.00 standard shipping within Australia

FREE standard shipping within Australia for orders over $100.00

Express & International shipping calculated at checkout

Stock availability can be subject to change without notice. We recommend calling the shop or contacting our online team to check availability of low stock items. Please see our Shopping Online page for more details.

In 1902, elegant Vienna is the city of the new century, the center of discoveries in everything from the writing of music to the workings of the human mind. But now a brutal homicide has stunned its citizens and appears to have bridged the gap between science and the supernatural. Two very different sleuths from opposite ends of the spectrum will need to combine their talents to solve the boggling crime: Detective Oskar Rheinhardt, who is on the cutting edge of modern police work, and his friend Dr. Max Liebermann, a follower of Sigmund Freud and a pioneer on new frontiers of psychology. As a team they must use both hard evidence and intuitive analysis to solve a medium’s mysterious murder-one that couldn’t have been committed by anyone alive. __________________________________________________________ THE MORTALIS DOSSIER- PSYCHOLOGICAL THRILLERS: THE CURIOUS CASE OF PROFESSOR SIGMUND F. AND DETECTIVE FICTION Summertime-the Austrian Alps: A middle-aged doctor, wishingto forget medicine, turns off the beaten track and begins a strenuousclimb. When he reaches the summit, he sits and contemplates the distantprospect. Suddenly he hears a voice. Are you a doctor? He is not alone. At first, he can’t believe that he’s being addressed.He turns and sees a sulky-looking eighteen-year-old. He recognizesher (she served him his meal the previous evening). Yes, he replies. I’m a doctor. How did you know that? She tells him that her nerves are bad, that she needs help.S ometimes she feels like she can’t breathe, and there’s a hammering inher head. And sometimes something very disturbing happens. She seesthings-including a face that fills her with horror… .Well, do you want to know what happens next? I’d be surprised ifyou didn’t.We have here all the ingredients of an engaging thriller: an isolatedsetting, a strange meeting, and a disconcerting confession.So where does this particular opening scene come from? A littleknownwork by one of the queens of crime fiction? A lost reel of anearly Hitchcock film, perhaps? Neither. It is in fact a faithful summaryof the first few pages of Katharina by Sigmund Freud, also known ascase study number four in his Studies on Hysteria, co-authored with JosefBreuer and published in 1895.It is generally agreed that the detective thriller is a nineteenthcenturyinvention, perfected by the holy trinity of Collins, Poe, and(most importantly) Conan Doyle; however, the genre would havebeen quite different had it not been for the oblique influence of psychoanalysis.The psychological thriller often pays close attention topersonal history-childhood experiences, relationships, and significantlife events-in fact, the very same things that any self-respectingtherapist would want to know about. These days it’s almost impossibleto think of the term thriller without mentally inserting the prefix psychological. So how did this happen? How did Freud’s work come to influencethe development of an entire literary genre? The answer is quite simple.He had some help-and that help came from the American filmindustry.Now it has to be said that Freud didn’t like America. After visitingAmerica, he wrote: I am very glad I am away from it, and even morethat I don’t have to live there. He believed that American food hadgiven him a gastrointestinal illness, and that his short stay in Americahad caused his handwriting to deteriorate. His anti-American sentimentsfinally culminated with his famous remark that he consideredAmerica to be a gigantic mistake. Be that as it may, although Freud didn’t like America, Americaliked Freud. In fact, America loved him. And nowhere in America wasFreud more loved than in Hollywood.The special relationship between the film industry and psychoanalysisbegan in the 1930s, when many EmigrE analysts-fleeingfrom the Nazis-settled on the West Coast. Entering analysis becamevery fashionable among the studio elite, and Hollywood soonacquired the sobriquet couch canyon. Dr. Ralph Greenson, forexample-a well-known Hollywood analyst-had a patient list thatincluded the likes of Marilyn Monroe, Frank Sinatra, Tony Curtis, and Vivien Leigh. And among the many Hollywood directors whosuccumbed to Freud’s influence was Alfred Hitchcock, whose thrillerswere much more psychological than any that had been filmed before.In one of his films Freud actually makes an appearance-well, more orless. I am thinking here of Spellbound, released in 1945, and based onFrancis Beedings’s crime novel The House of Dr. Edwardes. T he producer of Spellbound, David O. Selznick, was himself inpsychoanalysis-as were most of his family-and so enthusiastic washe about Freud’s ideas that he recruited his own analyst to help himvet the script. Hitchcock’s film has everything we expect from a psychologicalthriller: a clinical setting, a murder, a man who has lost hismemory, a dream sequence, and a sinewy plot that twists and turnstoward a dramatic climax. That this film owes a large debt to psychoanalysisis made absolutely clear when a character appears who is-inall but name-Sigmund Freud: a wise old doctor with a beard, glasses, and a fantastically hammy Viennese accent.Since Hitchcock’s time, authors and screenwriters have had muchfun playing with the resonances that exist between psychoanalysis anddetection. This kind of writing reached its apotheosis in 1975 with thepublication of Nicholas Meyer’s The Seven-Per-Cent Solution, a novel inwhich Freud and Sherlock Holmes are brought together to solve thesame case.The relationship between psychoanalysis and detection was notlost on Freud. In his Introductory Lectures, for example, there is a passagein which he stresses how both the detective and the psychoanalyst dependon accumulating piecemeal evidence that usually arrives in theform of small and apparently inconsequential clues. If you were a detective engaged in tracing a murder, would you expect to find that the murderer had left his photograph behind at the place of the crime, with his address attached? Or would you not necessarily have to be satisfied with comparatively slight and obscure traces of the person you were in search of? So do not let us underestimate small indications; by their help we may succeed in getting on the track of somethingbigger. Later in the same series of lectures, Freud blurs the boundary betweenpsychoanalysis and detection even further. He goes beyond pointingout that psychoanalysis and detection are similar enterprises and suggeststhat psychoanalytic techniques might actually be used to aid detection.Freud describes the case of a real murderer who acquired highlydangerous pathogenic organisms from scientific institutes by pretendingto be a bacteriologist. The murderer then used these stolen culturesto fatally infect his victims. On one occasion, he audaciously wrote aletter to the director of one of these scientific institutes, complainingthat the cultures he had been given were ineffective. But the lettercontained a Freudian slip-an unconsciously performed blunder.Instead of writing in my experiments on mice or guinea pigs, the murdererwrote in my experiments on men. Freud notes that the institute director-not being conversant with psychoanalysis-was happy to overlooksuch a telling error.In a little-known paper called Psychoanalysis and the Ascertaining ofTruth in Courts of Law, Freud is even more confident that psychoanalytictechniques might be used in the service of detection. He writes: In both [psychoanalysis and law] we are concerned with asecret, with something hidden… . In the case of the criminal itis a secret which he knows he hides from you, but in the case ofthe hysteric it is a secret hidden from himself… . The task ofthe therapeutist is, however, the same as the task of the judge;he must discover the hidden psychic material. To do this wehave invented various methods of detection, some of whichlawyers are now going to imitate.It is interesting that criminology and forensic science emerged at exactlythe same time as psychoanalysis. In 1893, Professor Hans Gross(also Viennese) published the first handbook of criminal investigation, a manual for detectives. It was the same year that Freud published(with Josef Breuer) his first work on psychoanalysis: a PreliminaryCommunication,

On the Psychical Mechanism of Hysterical Phenomena. Freud, largely via Hollywood, wielded an extraordinary influenceon detective fiction. But to what extent is the reverse true?We know that Freud was very widely read-and that he hadand Vivien Leigh. And among the many Hollywood directors whosuccumbed to Freud’s influence was Alfred Hitchcock, whose thrillerswere much more psychological than any that had been filmed before.In one of his films Freud actually makes an appearance-well, more orless. I am thinking here of Spellbound, released in 1945, and based onFrancis Beedings’s crime novel The House of Dr. Edwardes. The producer of Spellbound, David O. Selznick, was himself inpsychoanalysis-as were most of his family-and so enthusiastic washe about Freud’s ideas that he recruited his own analyst to help himvet the script. Hitchcock’s film has everything we expect from a psychologicalthriller: a clinical setting, a murder, a man who has lost hismemory, a dream sequence, and a sinewy plot that twists and turnstoward a dramatic climax. That this film owes a large debt to psychoanalysisis made absolutely clear when a character appears who is-inall but name-Sigmund Freud: a wise old doctor with a beard, glasses, and a fantastically hammy Viennese accent.Since Hitchcock’s time, authors and screenwriters have had muchfun playing with the resonances that exist between psychoanalysis anddetection. This kind of writing reached its apotheosis in 1975 with thepublication of Nicholas Meyer’s The Seven-Per-Cent Solution, a novel inwhich Freud and Sherlock Holmes are brought together to solve thesame case.The relationship between psychoanalysis and detection was notlost on Freud. In his Introductory Lectures, for example, there is a passagein which he stresses how both the detective and the psychoanalyst dependon accumulating piecemeal evidence that usually arrives in theform of small and apparently inconsequential clues.If you were a detective engaged in tracing a murder, wouldyou expect to find that the murderer had left his photographbehind at the place of the crime, with his address attached? Orwould you not necessarily have to be satisfied with comparativelyslight and obscure traces of the person you were insearch of? So do not let us underestimate small indications; bytheir help we may succeed in getting on the track of somethingbigger.Later in the same series of lectures, Freud blurs the boundary betweenpsychoanalysis and detection even further. He goes beyond pointingout that psychoanalysis and detection are similar enterprises and suggeststhat psychoanalytic techniques might actually be used to aid detection.Freud describes the case of a real murderer who acquired highlydangerous pathogenic organisms from scientific institutes by pretendingto be a bacteriologist. The murderer then used these stolen culturesto fatally infect his victims. On one occasion, he audaciously wrote aletter to the director of one of these scientific institutes, complainingthat the cultures he had been given were ineffective. But the lettercontained a Freudian slip-an unconsciously performed blunder.Instead of writing in my experiments on mice or guinea pigs, the murdererwrote in my experiments on men. Freud notes that the institute director-not being conversant with psychoanalysis- was happy to overlooksuch a telling error.In a little-known paper called Psychoanalysis and the Ascertaining ofTruth in Courts of Law, Freud is even more confident that psychoanalytictechniques might be used in the service of detection. He writes: In both [psychoanalysis and law] we are concerned with asecret, with something hidden… . In the case of the criminal itis a secret which he knows he hides from you, but in the case ofthe hysteric it is a secret hidden from himself… . The task ofthe therapeutist is, however, the same as the task of the judge;he must discover the hidden psychic material. To do this wehave invented various methods of detection, some of whichlawyers are now going to imitate.It is interesting that criminology and forensic science emerged at exactlythe same time as psychoanalysis. In 1893, Professor Hans Gross(also Viennese) published the first handbook of criminal investigation, a manual for detectives. It was the same year that Freud published(with Josef Breuer) his first work on psychoanalysis: a PreliminaryCommunication,

On the Psychical Mechanism of Hysterical Phenomena. Freud, largely via Hollywood, wielded an extraordinary influenceon detective fiction. But to what extent is the reverse true?We know that Freud was very widely read-and that he hadlished a memoir in 1971, which contains a very interesting aside. Thetwo men had been discussing literature, and Freud had expressed hisadmiration for several writers, most of them acknowledged mastersand writers of the first magnitude, such as Dostoevsky. However, bythe Wolfman’s reckoning at least, a lesser talent seemed to have gatecrashedFreud’s literary pantheon.Once we happened to speak of Conan Doyle and his creation, Sherlock Holmes. I had thought that Freud would haveno use for this type of light reading matter, and was surprised tofind that this was not at all the case and that Freud had readthis author attentively. The fact that circumstantial evidenceis useful in psychoanalysis when reconstructing a childhoodhistory may explain Freud’s interest in this type of literature.The Wolfman’s final observation is clearly correct. Crimes are likesymptoms, and the psychoanalyst and detective are similar creatures.Both scrutinize circumstantial evidence, both reconstruct histories, and both seek to establish an ultimate cause.If we broaden our definition of what might legitimately be calleddetective fiction and permit ourselves to consider works written evenbefore Hoffmann’ s Mademoiselle de ScudEry, then we encounter a storythat, without doubt, exerted a profound influence on Freud and thedevelopment of psychoanalysis. It is a story that British writer ChristopherBooker has called the greatest whodunit in all literature. It isone of the earliest stories of murder and detection ever recorded andhas a twist in the tale that still has the power to shock: Oedipus Rex bySophocles.When we meet Oedipus, there is a curse on his country. He is toldthat this curse will not be lifted until he has discovered the identity ofthe man who murdered his predecessor: King Laius, the former husband of Oedipus’s new wife, Jocasta. Oedipus follows clue after clue until his investigation leads him inexorably to a terrible conclusion.It was he, Oedipus, who killed the king. Laius was his father andOedipus is now married to his own mother.This classic tragedy is also an ancient detective story and gave itsname to the cornerstone of psychoanalytic theory-the much mooted(and even more misunderstood) Oedipus complex-a group of largelyunconscious ideas and feelings concerning wishes to possess the parentof the opposite sex and eliminate the parent of the same sex.I think there is something very satisfying about the relationshipbetween psychoanalysis and detective fiction. Freud influenced thecourse of detective fiction, but by the same token, detective fiction (inits broadest possible sense) also influenced Freud. And at a deeperlevel, psychoanalysis-a process that resembles detective work-discovers a whodunit buried in the depths of every human psyche.