Each week we bring you a sample of the books we’re reading, the films we’re watching, the television shows we’re hooked on, or the music we’re loving.

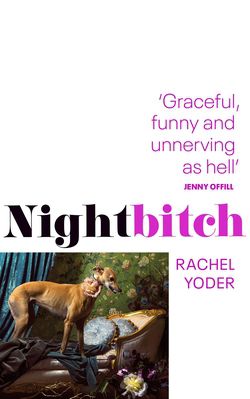

Joanna Di Mattia is reading Nightbitch by Rachel Yoder

I purchased a copy of Rachel Yoder’s debut novel Nightbitch after I was seduced by a simple 30-word blurb that managed to say a lot while not revealing much at all. Turns out, this is the only way to talk about this novel about a struggling mother, which pushes her joys and terrors into truly strange and wondrous territory. There are passages here that practically blew my mind with their audacity and intensity. Now, how to write about Nightbitch without revealing much more?

In Nightbitch, the mother in question, who remains nameless throughout, is exhausted and frustrated and lonely. An artist who no longer makes art, she’s home every day and night with her two-year-old son, while her husband is away at work for most of the week, every week. She feels detached from old friends and at odds with the other mothers she sees ‘coping’ around her. Pushed to the limit physically and emotionally, her body, which has already undergone a massive transformation, begins another one. Suddenly feral and fierce, the self-anointed ‘nightbitch’ embraces a new power, as a woman, wife, mother and artist.

Yoder’s highly inventive premise allows her narrative to travel in some weird, wild directions but it’s always grounded in something that’s honest and true, if frequently unspoken in the world. This dark, bloody fairy tale of modern motherhood is unlike anything else I have read this year. I can’t say much more. Just read it.

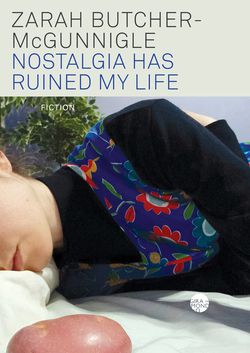

Oliver Driscoll is reading Nostalgia Has Ruined My Life by Zarah Butcher-McGunnigle

I’ve recently finished reading the utterly wonderful second book by the Kiwi author (who until the pandemic hit was living in Melbourne) Zarah Butcher-McGunnigle, Nostalgia Has Ruined My Life (Giramondo 2021). I loved her first book, a crisp and moving but gently absurdist poetry collection, Autobiography of a Marguerite, and have since been enjoying seeing her works move from things that look like poems to very sensitive and often darkly hilarious pieces that I guess you might call vignettes, or simply chunks of prose.

This new book is made up entirely of these prose pieces, which are all between half a page or two pages long. All the pieces are narrated by a world-weary twenty-something who struggles with relationships and work, in part because of an unnamed chronic health condition and in part because she has a vexed (and for the reader an amusingly vexing) relationship with her own wants and desires. She wants, the narrator says, children, and seems to want stability but, perhaps, in the absence of direction, simply wants to have wants. She is embarrassed by the idea of working towards anything. The desire for children seems no more pronounced that the desire to have, as she says at one point, scabs on her knees, or a bed that’s not covered in piles of dirty clothes.

The narrator is the kind of modern Bartleby-esque fringe dweller who, through her own passivity and perhaps curiosity, finds herself in a series of uncomfortable and darkly crushing situations. This book is always on the edge of cynicism, but the author is ultimately too sensitive to the fine and inherent detail of life for it to truly be that. The pieces frequently have non sequitur jumps between sentences, speaking to the nature of life; it being simply so much accumulation of things that happen, some droll, some tedious, some wildly unexpected.

When, in one piece, the narrator tells her ex-boyfriend that her housemates are thirty-five and forty-five, he says there must be something wrong with them if they can’t afford to live alone by that age. She says she won’t be able to live alone by the time she’s thirty-five because her illness prevents her from working full-time. He tells her she could become financially stable, she just has to think laterally. He needs to be harsh with her, he says. As each of these vignettes is a single – almost anachronistic – slice of life, there’s a suggestion of a kind of constant detached present. And although there’s little mention of climate change or anything else that imperils us, this book, even more than, say, Jenny Offill’s Weather, evokes a sense that many of us now feel of living without reliable hope in the future, with any kind of motivator constantly destabilised or pulled away.

This is one of the pieces in its entirety,

I feel productive taking out the empty cracker boxes and some of the dirty dishes in my room. Then I remember this isn’t productive because most people don’t have ten empty cracker boxes and twenty different mouldy plates in their room. Someone I loved once put their fingers in their ears while I was crying. I’m bored with myself too. I go to an interview for a babysitting job and they start digging a grave for their dying dog while I’m there. ‘Did you help dig,’ my ex-boyfriend asks. ‘I bet you didn’t.’ ‘Haha no, I didn’t,’ I say. ‘But I have a disability, I wouldn’t have been able to manage it.’ ‘I hope one day you’re healthy enough to dig a grave,’ he says.

Since finishing this book, I’ve found myself picking it up and reading pages at random and genuinely laughing out loud all over again. Though it’s a short book, and one that’s immensely readable, it’s a book that’s worth taking one’s time over and reading piece by piece the way you might read poetry.

Butcher-McGunnigle is a truly unique voice, and comparisons always sell authors short, but, nevertheless, this is definitely one for admirers Donald Barthelme, Lydia Davis, Tao Lin, Miranda July and those great poets who write finely crafted dramatically compressed prose, like Maggie Nelson, Anne Carson and Lyn Hejinian. This book also talks fascinatingly across the generations to another of my favourite books of 2021, the tonally altogether different but formally similar Whereabouts by Jhumpa Lahiri.