There’s a general perception that young boys today don’t enjoy reading as much as girls; that they find it more difficult to learn and are therefore reluctant to do it for fun. This turned out to be true in my house. I went from being the smug parent of a ‘natural’ reader (a girl) to the tortured parent of a boy who’d rather play with his pet rock than read a book. It took me a while to believe that the changes had to come from me rather than him.

My daughter learned to read by magic. One day, aged four, she could just do it. At first I assumed she’d simply memorised every children’s book we owned. I rushed out to buy new ones so I could see if her new skill was real. It was. I knew I hadn’t taught her to read with any special technique but I still allowed myself to feel pretty pleased with myself.

To assist my grip on reality, my son’s learning has been completely different. It’s consisted of arduous sessions side by side on the sofa, while I pointed to each word and held my breath. The long silences. The repetition. The eternally dull texts. His poor brain would whirr, he’d wriggle, demand water for his dry mouth, feign tiredness or illness (“I can’t read because I hurt my knee today”), and absolutely refuse to enjoy a single second of it.

We were both frustrated. I did what I swore I’d never do: compared his learning to my daughter’s. He was already two years older than she’d been when she ‘got it’, and showing no signs of progress. At six his capacity for narrative was so much greater than his ability to read that even when he managed to struggle to the end of a school book, he’d turn to me and say: “Well, that was boring.” I couldn’t really argue.

Because my whole life is children’s books, I began to worry that my two greatest loves would remain adversaries. I’m sure he could sense my concern. That, rather than his struggle to make sense of sounds and sight words - was where I was going wrong. I’m ashamed to say that he was probably worried about not pleasing me - the slight tension in my voice (“Come on, we just read this word”) and my finger jabbing the page a little too firmly.

Two little changes helped. First, I decided that whenever I felt frustrated, he must be feeling doubly so - my job was to help him relax and to show him the fun of learning a new skill. Humour was the key. Certain sight words became our “enemies” and I’d joke that we weren’t going to let “the” and “could” get the better of us. Making fun of oddities in the English language also worked. He’d pronounce “light” or “thought” with hard g’s by mistake and we’d spend a few minutes talking like this, eg. “Hey, I thuggut you turned the liggut on.” After some fun I’d remind him we needed to get back to the page. The next time we saw those words, I found he could recall the correct way almost immediately.

The second change I made was to cut him a fair deal but to keep it within the realm of books. If he’d read to me, I’d read to him. One school reader would equal one whole chapter of

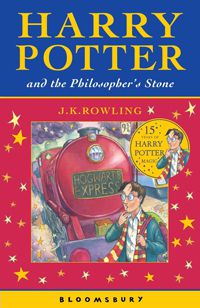

Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone

. This meant that his need for stories, characters and complex plots were being met in the same reading session. Although I’ve always read bedtime stories to him, I’d been choosing easy texts in the hope that he’d ‘magically’ learn to read them as my daughter had. I switched to sophisticated chapter books. Eventually I noticed that he was staring at the page over my shoulder and trying to find the words I was reading; he’d whisper “H-a-r-r-y”. He was coming to realise the benefits of learning.

As well as these changes, acknowledging his interests has been fundamental to his learning to read. His main source of joy and comfort is the animal world. It’s what makes him tick. So every book I gave him featured a relationship I knew he’d want to discover: a boy and an animal. For some kids, it’s the magic or the struggle against evil that makes them love Harry Potter - for my son it’s the fact that every student at Hogwarts has a pet-something; he’s basically a child-Hagrid. That’s his angle. It’s been vital to engaging him in texts that are within his reading skills.

Lucky for us that boys and their love of animals are a great feature of many Australian children’s stories. This feature has been a great help in showing my son that a book can be a friend, too.

Here’s a list of some we’ve enjoyed and others we’re saving for the next couple of years.

Just starting out, 4-6 years

The Rascal series

These stories about a little boy named Ben and his pet dragon Rascal are satisfying, easy reads. They contain good, solid messages without being preachy, and some toilet humour for good measure (yes, one of the first words my son was overjoyed to be able to read was ‘poo’). Try a neat box-set like More Little Rascals.

First chapter book, 4-8 years

Hey Jack: The New Friend

Sally Rippin’s companion series to the bestselling Billie B Brown is ideal for readers who need bigger stories but very simple text. Each book has only three chapters, each page only 10-15 words. In this story, Jack finds a puppy and desperately wants to keep it.

Longer story but illustrated, 6+ years

Weirdo

When a wall of text is off-putting, a diary-style book with short entries and plenty of cartoons is ideal. Comedian Anh Do hits the right note in his first chapter book, with plenty of humour. How did I get my son to read it? “The main character has a pet bird who poos on his head.” Done.

Confident readers, 8-12 years:

Storm Boy

A classic set in South Australia about a boy (who incidentally can’t read) and his beloved pelican, rescued as an orphaned chick.

Too Small To Fail

Gleitzman has the knack of writing the big stuff with the right amount of humour. In this book, a boy who is very rich in material things desperately wants more of the simple things in life: time with his parents, and a dog.

Light Horse Boy

If novels aren’t the key to a reader’s heart, narrative non-fiction might be. This book contains sketches, letters and photos alongside the narrative, which tells the story of two young boys, and their horses, serving in World War One.