During the month of October our Readings bookseller and resident horror aficionado, Joe Murray, is sharing his picks for the very best horror short fiction to get you in the mood for Halloween. You might have seen his recommendations on our socials during the month, but here's part two of his in-depth round up of why you need to read these masterful works of horror.

Read part one here!

Horror has always been a genre of experimentation and marginality. Consigned to the fringes of more ‘respectable’ literature, it is free to play with form and explore new territories: as long as it unsettles or terrifies, anything is fair game. Each of these works approach short-form horror from their own unique trajectories, revealing the strengths of their chosen form in the process.

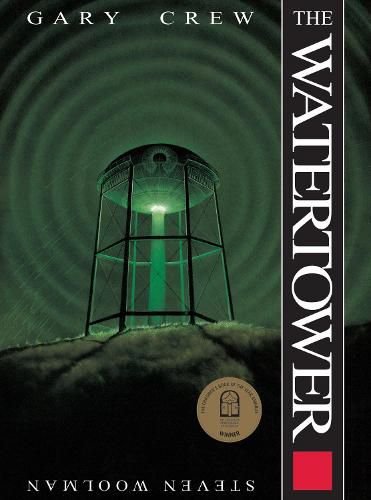

The Watertower by Gary Crew, illustrated by Steven Woolman

Unlike other stories I’ve mentioned here, I didn’t need to reread The Watertower to remind myself what about it is so terrifying – my memory could do that work for me. I don’t remember when I first read it but at some pivotal moment in my childhood it permanently lodged in my brain alongside countless unreasonably scary episodes of Doctor Who. Gary Crew’s narrative is unsettling enough, following two boys who take a dip in their town’s ominous water tower on a hot day and come back changed, but it is in Steven Woolman’s illustration that this picture book truly shines. The water tower is a constantly looming presence, subtly alien in its shape and eerie green glow, whilst the surrounding town feels off in some indistinct way: far too empty and still. However, what sticks with you the most are the tiniest details: the water tower bears a strange symbol and the closer you look at Woolman’s illustrations, the more you see it everywhere else. Despite its picture book status, I sincerely believe this story is as good as the best horror stories and uses its medium to incredible effect.

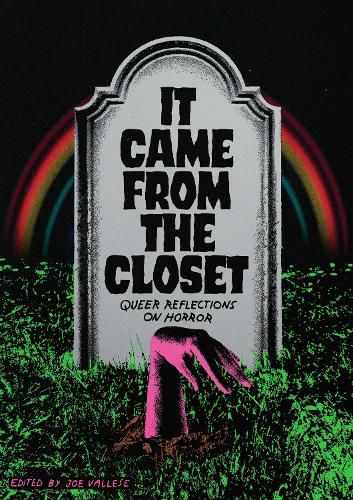

It Came from the Closet: Queer Reflections on Horror edited by Joe Vallese

Uniting the insightful meditations of a personal essay with a rich variety of horror films, this collection gathers together a brilliantly diverse mix of queer authors to reflect upon their life experiences through the lens of popular horror. As a genre, horror has a complicated relationship with queerness: even as it draws fear and disgust from failures to conform to cisgender heteronormativity, it also invites a sympathy with the monstrous that appeals to anyone othered by society.

It is this conflict that each author grapples with in their unique way, finding resonance in horrors old and new, from Carmen Maria Machado’s sharply funny discussion of bisexuality in Jennifer’s Body, to Tucker Liebermann’s account of a troubled friendship that he only finds himself able to articulate through the proxy of A Nightmare on Elm Street. However, if one essay stuck with me the most, it would be Laura Maw’s essay on The Birds, a simple but haunting reflection on the tragedies that stand in the way of queer possibilities and a heartbreaking depiction of the desperation that comes from wanting a happier ending.

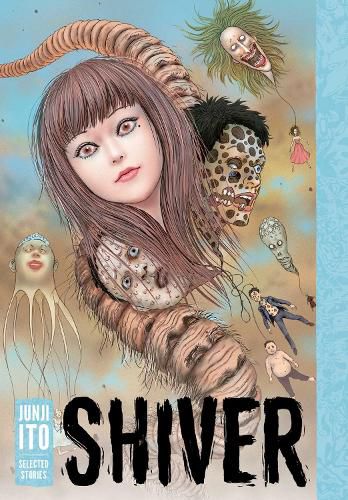

Shiver by Junji Ito

Junji Ito is widely renowned as a master in the art of horror manga, known for his epic sagas, ambitious adaptations and especially his terrifying short stories. This collection boasts many of his best, bursting with terrors that relish in the unique possibilities of the comics form. Ito hides overwhelming tableaus of horror behind the turn of the page, his meticulously detailed black and white compositions capable of making any image terrifying, from a greasy little brother to a model’s sharklike smile. Indeed, this talent for the visually horrifying allows Ito’s stories to explore unusual territory for horror, freeing his narratives to strike strange paths, assured that the reader will remain on the edge of their seat.

The exemplary ‘Hanging Balloon’, displays this quality to great effect, consistently terrifying despite its decidedly odd premise: soon after a high-profile suicide, Japan is overrun by hordes of giant, noose-laden balloons bearing the faces of their chosen victims. Ito’s illustrations lend the tale a haunting, hopeless quality and its grotesque closing image – a common ploy from an author who is rarely kind enough to write a happy ending – has stuck with me for years.

There is No Antimemetics Division by qntm

Although it will require some explanation and patience, if you’re willing to take the plunge, the world of SCP will reward you with some of the best, most interesting horror writing the internet has to offer. In fiction, the SCP Foundation is a shadowy organisation devoted to protecting the normal world from a whole host of anomalous entities, ranging from the perplexing and harmless to the terrifying and world-ending. In reality, the SCP Foundation is a collaborative writing and worldbuilding project in which countless authors and artists contribute monster profiles and short tales to an ever-expanding online database.

Browsing the SCP wiki brings all the bewildering joy of a Wikipedia deep dive as you follow each link, stumbling upon an endless succession of inventive horrors which often make great use of their digital presentation. However, if you need a good place to start, you can’t go wrong with There is No Antimemetics Division by user qntm, a gripping sequence of interconnected tales about monsters that prey upon the memory and the brave operatives determined not to let them be forgotten, starting with one researcher’s near-lethal first day.

Over the past decades, the horror short story has experienced a golden age of sorts thanks to a proliferation of brilliant, inventive collections from emerging female voices, writing in both English and translation. Whether their stories embrace, subvert or totally reject the traditions of horror, they all offer visions of unease and haunting that are hard to ignore and harder to forget. In an industry dominated by the novel, they demonstrate what the short story collection has to offer: exhilarating variety shaped by an author’s singular voice.

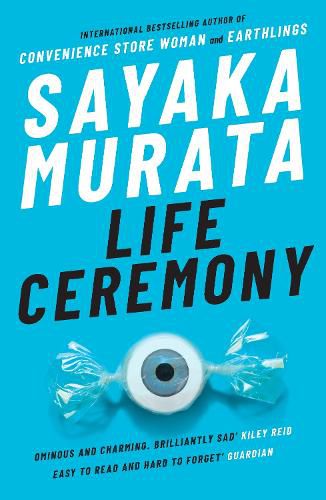

Life Ceremony by Sayaka Murata, translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori

As I was reading this brilliant collection in preparation for writing this, I found myself with a growing sense of unease entirely unrelated to Murata’s stories themselves: the more I read, the more it became clear that her writing didn’t quite fit in with the rest of the horror listed here. Instead, this collection is much more devoted to strangeness and alienation, returning again and again to characters who are living on the brink of social normality in one way or another. Fear and dread are less her explicit goal than the natural outcome of the social situations Murata arranges – even when the subject matter enters territory more aligned with the genre, such as in the title story’s ritualised cannibalism, her writing has a satirical warmth to it.

At least, this is what I thought before I reached ‘Hatchling,’ the penultimate story in the collection, and its most horrifying by far. Although it begins with an amusing premise, as a woman so devoted to fitting in that she has developed numerous distinct personas now faces their imminent collision at her wedding, by the end I was left overwhelmed by the existential horror of identity.

Salt Slow by Julia Armfield

Although she truly emerged into prominence with the genre-bending horror of Our Wives Under the Sea, when I think of Julia Armfield, I’ll always think about the stories of Salt Slow. With its grad-student Frankensteins and shadowy manifestations of living sleep, Armfield’s debut collection is inundated with gothic images, but her gorgeous writing style lends even the most gruesome scenes a sense of beauty and grace, trading immediate shock for a lingering disquiet that persists long after the story’s end.

Femininity and desire, especially sapphic desire, are core pillars of these stories, which explore loves gained and lost and depict bodies that are exalted and profaned in equal measure. The story ‘Cassandra After’, for example, blends grotesque body horror with an achingly grounded story of mourning and return that represents a fascinating precursor to Armfield’s following novel. However, my pick for Armfield’s best is easily the title story: in a world long since flooded by torrential rain, a couple navigate the endless seas, silent witnesses to the water’s slow transformation of what little life remains, including their own unborn child. Part Lovecraft, part Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, ‘salt slow’ is exactly what I search for from horror.

Her Body and Other Parties by Carmen Maria Machado

Carmen Maria Machado has quickly proven herself one of the most exciting new voices in short form horror after breaking into prominence with this collection, which lays bare the various violences inflicted upon the female body across a host of uneasy, daring tales. Although some are boldly direct, most toy with narrative structure, challenging the reader and unsettling their expectations about traditional storytelling. The opening story, ‘The Husband Stitch,’ sets this tone perfectly, describing an erotic, fairytale courtship that is inevitably stained by male entitlement. Machado writes with a sharp, almost vitriolic wit, that reminds the reader again and again of the grim fates that await women who dare to hope for more from their stories.

However, the tale that feels most reflective of Machado’s unique inventiveness is the formally radical ‘Especially Heinous.’ This lengthy and compellingly bizarre saga consists of 272 gestural, haunting episode summaries from a version of Law and Order: SVU seemingly drawn from a reality that is a gothic echo of our own. Over countless episodes, detective Benson and Stabler face uncanny doppelgangers, ghostly children and the unbearable metatextual weight of a show that has been submerged in cruelty for entirely too long.

Mouthful of Birds by Samanta Schweblin

If you’re looking for a masterclass in atmosphere and tone, this haunting collection from Argentinian Samanta Schweblin offers exactly that across its twenty expertly told stories. Reading this collection feels just like a night of bad dreams – strange, cryptic and unsettling – that are never so direct as to be explicitly nightmarish. Instead, Schweblin’s horror perpetually lurks in the background: it is obscured, displaced or anticipated, existing more in the reader’s mind than on the page. Holes are dug for inexplicable purposes, businessmen await a train that never stops, a man is left to the mercy of a pack of dogs. The story ends and the reader wakes up, only to tumble into some new darkness. And just like a night of troubled sleep, Schweblin’s collection has its preoccupations that emerge again and again: gender, poverty and most apparently, the fraught relationship between parents and children. This latter theme animates multiple stories about regression and transformation and also represents the beating heart of the collection’s powerful title story, which takes the brittle tensions of adolescence and renders them unbearably grotesque.