So frequently I feel that these days I’ll read a book, close it, and say ‘Wasn’t that good’, and then move on without a backwards glance. But what about those books that are impossible to forget? Those books that kick you in the guts, jump up and down on your heart and stomach, refuse to leave you alone?

Inspired by the upcoming Love Letter to a Book series at this year’s Melbourne Writers Festival, below are some of the books that for one reason or other, won’t leave me alone.

Atonement by Ian McEwan

I first read Atonement when I was maybe about 16 or 17 over the course of a few very intense, boiling hot days at my parents’ rural property over the summer. I know, very appropriate. In Atonement, 13-year-old Briony Tallis’s imagination runs away with her, leading her to commit a heinous crime on the hottest day of the summer and set in chain a series of terrible events. The language in this book – my god. McEwan expertly sets up Briony’s richly imaginative and over-dramatic child’s inner world, setting it off perfectly against the undercurrent of very adult tension simmering just under the surface of this pre-WWII wealthy family estate. If you haven’t seen it, the film adaptation is really special too. I remember being struck with a particular line in the director’s commentary where he’s talking about the overly floral set design of the family house. He describes the set design as deliberately ‘kitsch’, elaborating that he sees kitsch as being ‘ripe to the point of rotten’. That’s exactly the tone of the prose. The simmering anger, the sexual tension, the class struggle – it’s all bubbling away beneath this over-heated summer’s night. Love it.

White Houses by Amy Bloom

‘The first thing I knew in this world was that I was alone and unseen. Then I knew I was not. You are not just my port in the storm, which is what middle-aged women are supposed to be looking for. You are the dark and sparkling sea and the salt, drying tight on my skin, under a bright, bleaching sun.’

In 1933, President Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt took up residence in the White House. With them went the celebrated journalist Lorena Hickok – Hick to friends – a straight-talking reporter from South Dakota, whose passionate relationship with the idealistic, patrician First Lady would shape the rest of their lives. I feel like I’m frequently lamenting the lack of nuanced portrayals of women in their middle years and old age. But White Houses is what I was looking for. The intricacies, dignities and indignities of Eleanor and Hick’s affair will wound and devastate even the stoniest reader. This novel is not shy – it lays its soul bare alongside a forbidden love affair to rival any other in literature, made all the more moving for the circumstances of its characters.

Cold Mountain by Charles Frazier

Wounded in the Civil War, Southern soldier Inman deserts the massacre of the battlefield and walks all the way home to Cold Mountain. He hasn’t been home for years, and doesn’t even know if his love, Ada, is still alive. As he walks, he encounters extraordinary hardship and struggle, both in himself and in the pillaged, bleeding landscape around him. There are two particular moments (as if you could pick just two) in this novel that won’t leave me alone. The first is when Inman, starving and near dead, encounters a bear and her cub on the edge of a cliff. He locks eyes with the mother bear and finds a moment of extraordinary kinship and fellowship – his Native American friends have shown him that the bear is his spiritual totem animal – and then he lets her charge him, knowing that if he moves at the right moment, she’ll fall over the cliff and he’ll be able to eat her cub, and live. In the second, Inman (once again nearly dead from starvation), has finally reunited with Ada – but their relationship is tender and precarious and a huge unknown, and as he sits by her campfire, he decides that if she doesn’t want him, he will continue to fast and therefore be able to pass into the mountain and join the long-lost Native American tribe in the mythical realm on the other side.

Wild by Cheryl Strayed

I don’t think everyone feels the way that I do about Wild. Maybe it was just one of those ‘right place, right time’ reads. But something about Cheryl Strayed’s memoir about walking the 1100-mile Pacific Crest Trail after her mother’s death sends her into a spiral of self-destruction really struck a chord. I’ve heard some people say that they were frustrated that Cheryl didn’t seem to grow by the end of her journey, but I’d disagree. I think the moment where she realises that maybe she has nothing to atone for, nothing to ‘overcome’ – that maybe she’s alright the way she’s always been, mistakes and messes and all, is powerfully poignant. I’ve waxed poetic about this incredibly stirring memoir before – check out my ridiculously gushy ‘What We’re Reading’ post from earlier in the year here.

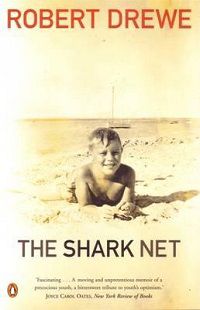

The Shark Net by Robert Drewe

Okay, this was my gateway non-fiction, and it’s also the book I recommend to people who want really (really, really) well-written true crime. It’s about Robert Drewe – one of Australia’s most famous writers – and his life as a young boy, then teenager, growing up in Perth, the world’s most isolated city. The catch is that as he’s growing up, a prolific serial killer is prowling the streets of Perth. One of young Drewe’s friends is a victim. The killer? Eric Cooke – an employee of Drewe’s father, and well-known to the family. This is a coming-of-age story like no other; told with Drewe’s trademark unforgettable, evocative prose. The bit (bits) that stay with me: little Robert quivering with fear in his childhood bedroom every night, listening to the lions in the Perth zoo roar from across the river, terrified that they’re going to get into his bedroom; Drewe’s imagining of the killer, ‘Saturday Night Boy’, swimming across the Swan River in the middle of the night, heedless of potentially falling victim to sharks, boats or drowning, heading out to gatecrash another party while his wife sleeps in bed at home.