Nicolai Lilin’s memoir

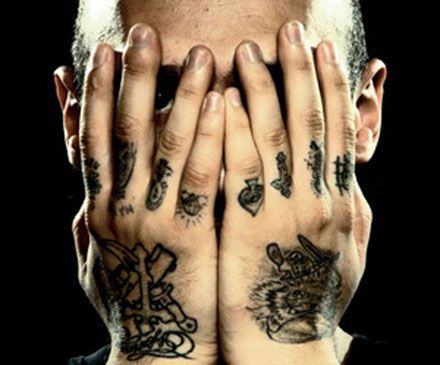

Tattoist and writer Nicolai Lilin.

What was the reaction to your book from the people you grew up with?

My mother says that I speak too much and that in describing many situations I got little right. Before he died, my grandfather knew that I was going to publish my book and was happy. In the telephone call I placed from Italy to Transdniestria a few days before his death he told me: ‘I am happy that you have written this book and that I am also present in the story. In this way, after my death I will continue to live on in your book and in the thoughts of many people.’

Your youth seems to have been extremely dangerous and yet remarkably secure thanks to the many codes and rules you were bound by – do you think it’s possible to have one without the other, or does the danger of a criminal life require the tight connections of family and community to make it survivable?

Although it could seem ‘extreme’, my childhood instead appears to me full of good memories and I remain a happy person myself. Like many humans, I too have nostalgia for my childhood, for the people I knew, for old friends, for past times. I have not told a story of criminality: mine is a story of resistance to the regime that suppressed us; all opponents were defined as ‘criminal’ by the authority of this regime. In resistance it is very important to have a foundation of rules which help to create an alternative system to the dictatorship. Every human society has rules, and every rule somehow links the family nucleus with society, protects it but also demands its input. This schema is present in every human society, from primitive society through to modern society.

Is it fair to say that your community developed its strict bonds to aid their resistance – to communism and the tsarist regime before it? And if those bonds had helped the community survive so much, why did it die out?

In my book, I sought to bring back what was once the Siberian criminal community. I based all my accounts on stories I heard from the elderly people from where I grew up, joining these stories with my own personal experience, with the experience of men I knew, friends and relatives. In the book, the community appears as if it still existed and as if it were still powerful. In truth, I was born at the moment when the last generation still bound to the old community and the old rules was dying out. I was 9–12 years old; they were 85–90. My book is based on the memories elderly people shared with a child. I know nothing of the history; it doesn’t interest me to conduct an analysis of the situation, to judge or to justify someone. I believe that the community has died out because it had to happen this way, because their rules were too inflexible and no longer answered to the needs of the younger generations. My grandfather once said of the disappearance of the Siberian community: ‘When summer arrives, the stoat must change its coat, even if it likes the old one.’

Are there any remnants of the Siberian community in Transdniestria today?

The elderly have died or are about to; everything has disappeared because there are no longer young people interested in the ancient rules. In Transdniestria today money, fancy cars and mobile phones are more important than respect, honour and dignity.

What advantages do you think your upbringing had over a more Western childhood?

Even if I grew up in a difficult situation, I believe that I had a normal experience for the situation in which I was born and grew up. What is important is having a direct relationship with the elderly, listening to them and learning from them how one stands in the world. When the elderly are abandoned to aged-care facilities and the young people think they are more intelligent than everyone else, that’s when the problems begin, the country’s politics go bad, the economy deteriorates, everything goes to pieces because one cannot manage life without the experience of someone who has lived it. I believe that the whole world today needs to listen to the elderly and to discuss its very future with them; in this way, we will attain salvation.

Russian criminal tattoos are known for their ability to tell a story. Are there similarities between your work as a tattooist and a writer?

In Russia, there are different traditions of tattoos, some of which are also linked to criminal societies. If you see a tattooed Russian, it doesn’t mean that he’s a criminal. He could be a Siberian hunter or a pagan or a member of some old Christian community. The tattoo is a mode of communication and is very important to me personally. With literature it is very similar, the fact that in writing a novel you present your own life to others, just as when you get a tattoo.