Jon Doust’s debut book, Boy on a Wire has been longlisted for the 2010 Miles Franklin Award. A darkly funny coming-of-age story, it’s a ripping read with echoes of Craig Sherborne’s Hoi Polloi. Jo Case spoke to him for Readings.

The cover of your book says it’s a memoir; on your website you’ve said it’s ‘a sort of fiction based on a kind of life’ you once knew. What is it – fiction or memoir? Or something in-between?

It is something in between. As a story teller I like to start from a recognisable and accepted truth, then play, embellish and twist. In the final script, some truths will remain, but much will have been through the ringer of fiction. In Boy on a Wire I left in a couple of real names, just to add to mystery and confusion.

Your main character, Jack Muir, reflects that in boarding school, ‘Only those who can find the mean streak in them survive.’ How is this reflected in the book, and particularly in Jack himself?

It is reflected in Jack’s anxiety about his life in the boarding house, and his life in Genoralup with his family. One of my abiding memories is the constancy of fear: you were frightened of bigger boys, of teachers, of your mum and dad, and the butcher, the newsagent, the travelling shearer’s bullying son.

You brilliantly inhabit the character of Jack, a version of your childhood self, in this book – the ‘voice’ is pitch-perfect. Was it difficult to find a way of writing that character, or did it come instinctively?

Yes, it came instinctively. I think Jack was waiting for me to let him out and when he got his opportunity, he took it without hesitation or fear. The great thing was, he didn’t frighten me. In fact, I encouraged him.

One thing that’s appealing about Jack as a character is his blend of naivety and knowingness. Do you think this is something that is particular to him, or is it characteristic of certain stages of childhood and adolescence?

It is as I remember it and as I see it now in others. I have a lot of young friends and that’s how they are, seemingly all knowing in a couple of aspects, and in others just at a level of understanding you would expect for their age group. Sometimes it’s confusing, but I enjoy the mixture. I see it in most people, at all ages, but I think it is more noticeable in the young.

Jack Muir’s ‘biggest weapon’ is his tongue; his sense of humour is integral to his arsenal. Similarly, the book is written with an eviscerating black humour. Did you deliberately use humour as a weapon – or as a tool to get across your point of view – in your writing?

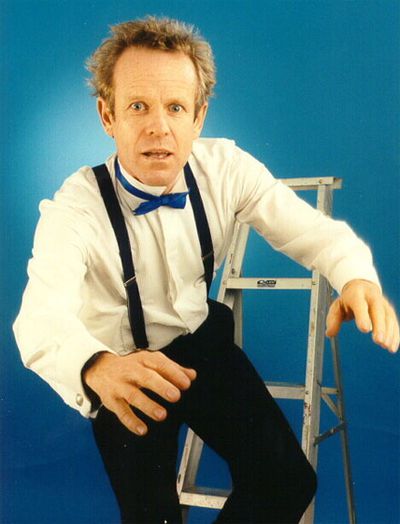

My family have always used humour to cope with illness, failings and flaws and I have a background in stand-up comedy. Once I realised I did not want to live in Melbourne and pursue a career in comedy, I began to look for other ways to use my skills. My personal sense of humour has a darkness and I am a regular user of it as a survival tool.

Jack draws on a range of heroes (including Atticus Finch, James Bond, Jesus and the Phantom) to construct his own version of manhood, different to his Dad’s John Wayne mould. The question of how to be a man, and what kind of man to be, seemed to be central to the book. Was that a driving force, and if so, what appealed to you about that question?

The driving force was probably the lack of a meaningful conversation between my father and I or anyone of his generation. It seemed natural that I turn to fictitious men and boys for guidance. I arranged for Jack to experience the same need. I’m not sure it is appealing, I think it is just how it is. I still sometimes long to meet older people with innate wisdom uncluttered by judgment or dogma.

What was it about your own boarding school days that drew you to revisit them for the book? What made them such compelling material?

My first two years I remember as being reasonably good fun, I think I even enjoyed the occasional, deserved canings, but the lasting impression was the cruelty to boys who could not stand up for themselves. People often ask if boarding school scared me and my answer is always the same: the biggest scar it left on me was the scar I saw it left on others. Over the years I have met many boys who remain scarred and their continued suffered has puzzled and saddened.