Practising speech pathologist and guest blogger Alison Clarke clues us in on the strategies that help children read and spell effectively, right from the start.

Language is natural. Reading is not.

Reading aloud to children is a great way to help them develop their vocabularies and other language skills, learn about the real and imaginary worlds, and share and discuss ideas and emotions.

Listening to adults read lets young children discover subjects like volcanoes, Rumplestiltskin, unicorns, astronauts, and the extraordinary life of Frida Kahlo, long before they can actually read such long, hard words themselves. It gets them excited about reading.

But reading aloud to children does not teach them how to read. Young children are predisposed by evolution to learn to talk naturally, if exposed to a spoken language. They are not predisposed by evolution to read or write. In evolutionary terms, written language is a very recent invention, and must be taught and learnt.

For some children, this is very hard. Not learning to read and spell well can make school a miserable experience, and can have a devastating impact on self-esteem. It’s vital we prevent reading failure by teaching children to read and spell effectively, right from the start.

Aligning teaching with research

For decades there has been a significant gap between scientific research and mainstream classroom practice in the teaching of reading and spelling, fuelling the Reading Wars. Children have often been taught to read by memorising high-frequency words, guessing words from pictures and context in repetitive/predictable books, and learning the “sounds of letters”, but not much more about our spelling system.

Happily, many schools are now aligning early literacy teaching more closely with the scientific research, by introducing much more systematic, thorough teaching about how sounds are represented by letters and letter combinations (phonics), and how words are built from meaningful parts (base words, prefixes and suffixes).

Decodable books are a key ingredient in this teaching, since they contain the sound-spelling relationships and word parts that children have been taught. They provide the reading practice for phonics lessons, reinforcing strong reading habits (sounding out unfamiliar words) not weak reading habits (guessing).

This teaching is, in the words of leading reading researchers Catherine Snow and Connie Juell, “helpful for all children, harmful for none, and crucial for some”.

Many children find it very hard to analyse the sound structure of words, since sounds tend to smoosh together in spoken words, and are transient and invisible. Pulling words apart into sounds in order to represent them with letters is hard enough in languages with simple spelling patterns, like Turkish, Spanish and Korean. English has an additional problem.

English spelling is very hard

English is a mashup of the languages of the Anglo-Saxons, Vikings, Norman French, Romans and Greeks, with words borrowed from many other languages. This gives English an exceptionally difficult spelling system.

We have 44 speech sounds but only 26 letters, so must use letter combinations to spell many sounds.

We can use one, two, three or four letters to spell a single sound – think of the “I” sound in ‘my’, ‘pie’, ‘night’ and ‘height’.

Many sounds are spelt several ways, for example, the sound ‘er’ has five common spellings, as seen in the words ‘her’, ‘bird’, ‘turn’, ‘work’ and ‘earth’.

Spelling often depends on a sound’s position and neighbours, for example, we spell ‘er’ as ‘or’ after the sound ‘w’, as in ‘worm’, ‘worst’ and ‘worth’.

On top of that, many spellings are used for more than one sound – think of the ‘ch’ in ‘child’ (from Anglo-Saxon), ‘school’ (from Greek) and ‘chef’ (from French).

We also have many special spellings for meaningful word parts, like the ‘ed’ for past tense, regardless of whether it is pronounced ‘t’ as in ‘packed’ (a homophone of ‘pact’), ‘d’ as in ‘binned’ or ‘ed’ as in ‘flitted’.

How do decodable books help?

Decodable books strip back English spelling complexity and allow children to practise just a few sound-spelling relationships at a time.

Representing one abstract thing (a speech sound) with another one (a letter) is hard enough without having to learn a whole lot of them at once, and without really knowing what the letter groupings are. Decodable books solve this problem using an explicit and systematic approach, and don’t leave learning to read to chance.

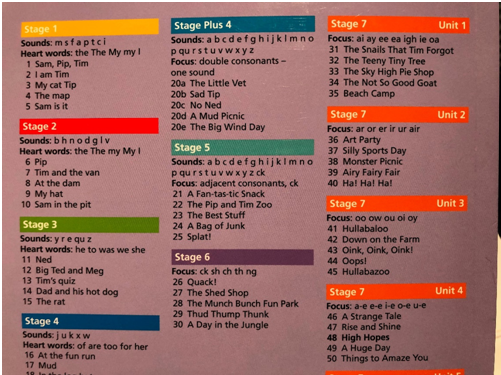

If you look on the back of a decodable book, you’ll see which sound-spelling teaching sequence it is part of, and where it fits in this sequence. For example, here’s the back of one of the Pip and Tim books available at Readings.

Decodable books are essential for most children with learning difficulties, so I use them a lot in my speech pathology practice. I’ve usually had to buy these books from specialist suppliers, so I’m delighted that decodable books are now available at Readings Kids.

When we learn to read, we build a new brain circuit

When we learn to read, we hijack the area of our brains ordinarily used for recognising faces and objects, and repurpose it to connect visual and speech/language brain areas. By linking speech sounds and letters, we can start to slowly, sequentially sound out words.

Once we can turn print into sounds in this way, we can hear the words and start to understand what we are reading. As we learn more and more about sounds, spelling patterns and word parts, we can teach ourselves to read new words.

As we heighten our awareness of speech sounds, learn the spelling patterns that represent them, and do a great deal of practice, we start processing all the letters in familiar printed words at once, instead of having to work slowly through words from left to right.

This allows us to recognise familiar words, and link them directly to meaning. This in turn frees up cognitive resources, making it easier to think about what we are reading, and read for enjoyment.

Prevention is better than cure

As a speech pathologist who specialises in working with struggling readers and spellers, I see many children (and a few adults) who failed to build their reading brain well in their first three years of schooling. Now their brains are less flexible, so the task is still doable, but it’s much harder.

I wish their parents had read a blog like this one when they were aged five, insisted that they be taught to sound out words systematically and explicitly, and given them decodable books to practice these patterns. Many of them would now not need my help, and those that still do would be less far behind their classmates, and less miserable.

Most children will learn to read no matter how they are taught, but without explicit teaching about sounds, letters and word parts, many will struggle with spelling, and a significant minority will read poorly or fail to learn to read well.

Decodable books in every early years classrooms and the homes of five-year-olds would help prevent reading failure. They would allow many more children to quickly and successfully transition from learning to read to reading to learn, and reading for pleasure.