To celebrate the release of her new book, Corners of Melbourne, award-winning author Robyn Annear very kindly investigated the history of a street corner well known to Readings Carlton and Kids customers – Carlton’s Tyne Street. Here, Annear takes us back in time and along Tyne Street, revealing a healthy locale with a surprisingly colourful history.

If we’re talking street corners, Readings Carlton is ideally positioned. The two Lygon Street shops occupy facing corners of the west-running Tyne Street. Sometimes a corner is the story; other times it’s a hinge, a turning-point. Here, the bookshop corners form an aperture onto Tyne Street.

There used to be 21 cottages in Tyne Street. Built in the 1860s of timber or brick, some with bluestone fronts, most had just two or three rooms and sat on narrow allotments, each with a yard behind. When one came up for sale or rent, it would invariably be advertised as ‘snug’ or ‘compact’, ‘well suited to the wants of an artisan with a small family’, or even as ‘A Poor Man’s Home’. That was no pejorative; it meant just what it said. What’s more, Tyne Street was a healthy locale, ‘being on the crown of the hill … where you can enjoy the sea breeze combined with good drainage’. It was close to the city – and to Lygon Street, ‘the Bourke-street of Carlton’.

Building regulations enacted in 1916 prefigured the inner-city ‘slum clearances’ of the mid-20th century. When the city council proposed that any residential street less than 30 feet (roughly 9 metres) wide be classified a slum and targeted for eradication, voices were raised in Tyne Street’s defence. It may have been just 18 feet (5.5 metres) wide, but Tyne Street, they said, was no slum. Its cottages were clean and inhabited by ‘decent people’. No matter: under the new regulations, the building (or rebuilding) of housing on narrow streets was outlawed. Thereafter, the aging cottages in Tyne Street would be advertised ‘for sale or removal’. By 1950, their number had dwindled to 10; by the mid-1970s, only four remained.

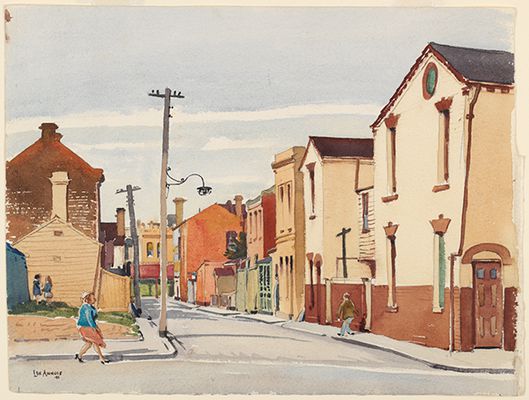

Len Annoise, Tyne Street, Carlton, 1941. Courtesy of State Library Victoria.

Who lived in Tyne Street’s cottages? Over the years, wives and widows predominated, some living snug with families of their own, others taking in boarders. There were dressmakers and milliners, wet-nurses and midwives, a hay merchant; a woodyard, a dairy, stables.

Some of the cottages were dignified with names. At the rear of Readings Kids was Violet Cottage. Midway along, a Miss Warner ran a pocket-sized school (or ‘Select Preparatory Establishment’) in Alberta Cottage and, near the far end, photographer J.P. Lind had his travelling portrait saloon moored at Ambrose House – with Crawcrook House tucked behind.

Widow Clarissa Stringer was threatened with eviction from her Tyne Street cottage, but defied the bailiffs with the help of the 200-strong Salvage Corps, a vigilante squad based at Trades Hall. An old soldier who lived and died in Tyne Street had been one of the ‘gallant six hundred’ immortalised in Tennyson’s poem, ‘The Charge of the Light Brigade’. Opposite him lived the Nuttall family, who placed this notice in the Lost & Found column of the Age in March 1878 –

Lost, Tyne-street, Carlton. Mark Cyril Nuttall, 6 years, dark hair, large dark eyes, pale face. Had on tweed knickerbocker suit, white straw hat.

Nothing else is known of the lad’s disappearance, but he must have been found safe, since he went on to play half-forward flank for Carlton in the footy season of 1893.

Not lost but found in Tyne Street was Jacko, a valuable talking myna, missing (presumed stolen) from his cage by the door of the Royal Hotel in the city. Police detectives found Jacko in the cottage of Jessie Smith. Her son, Moss, aged 22, claimed he’d been walking along Argyle Place when a voice called out, ‘Go and get work, you loafer!’ and he spied Jacko ‘leering’ at him from a fence. He easily caught the bird and took him home. The detectives, disbelieving Smith’s story, charged him with stealing Jacko, and he was sentenced to three months’ gaol.

Jacko was in the courtroom for Smith’s trial, calling out from his cage as each witness took the stand, ‘Hello! What’s your name?’ The case of the garrulous myna, making headlines nation-wide, led to another news-worthy discovery. A Sydney law firm had been seeking the whereabouts of Annie Wallace, who’d been left a fortune by a former suitor. Listed among the witnesses in a report of Smith’s trial was the very same Annie Wallace, now a cook at the Royal Hotel, widowed with nine children and an invalid father to care for. Though she hadn’t heard from her old sweetheart for more than 20 years, he’d bequeathed her a blue-ribbon property portfolio.

Back on his old perch at the Royal Hotel, Jacko’s celebrity seems to have gone to his head. Whenever a stranger approached, he’d fluff himself up and squawk, ‘I’m a hot thing! Hands off!’