It’s a really interesting thing, isn’t it? To write a book and feel so different about it all the time, and not know some of the answers to the questions,’ 23-year-old debut author Ellen van Neerven confides early in our conversation. She is shy but candid over the phone, often surprising me by asking to hear my own thoughts in return, which makes it as much a pleasure to speak to van Neerven about her breathtakingly good work of fiction, Heat and Light, as it is to read it.

An earlier version of the book won van Neerven the David Unaipon Award – Unpublished Indigenous Writer in the 2013 Queensland Literary Awards. She then worked closely with her editor at the University of Queensland Press to reshape the book into its present structure, bundling the short stories and a novella-length piece into three separate but thematically linked sections. It’s difficult to categorise the book – a story collection? A novel-in-stories? Van Neerven agrees: ‘I think we should just call it fiction.’ Even before she won the David Unaipon Award, her writing was receiving recognition, with one of her stories collected in The Best of McSweeney’s, edited by Dave Eggers.

Heat and Light starts with a set of stories about members of the Kresinger family, who are re-evaluating their lives in the wake of new knowledge about their true grandmother, Pearl, and the curse she inherited and visits upon the family over generations. Pearl is Bundjalung, the ‘kind of woman that draws men like cards’, and the violence she endures at the hands of men has consequences far into the future. ‘So much is in what we make of things,’ the narrator says at one point, reflecting on her father’s refusal to admit that Pearl is his mother. ‘The stories we construct about our place in our families are essential to our lives.’

The book’s middle section, ‘Water’, is a longer work of speculative fiction, which van Neerven says some mentors encouraged her to develop into a stand-alone novel, though she is now glad she placed it at the book’s centre. It’s a brilliant parable set in the near future, when Australian politicians have decided to give Indigenous people a ‘second country’ called ‘Australia2’ in a horribly misguided attempt at making reparations. Indigenous people can apply to live in this country, but they must ‘show how they have been removed or disconnected from their country – priority given to those who don’t even know where they’ve come from’. This ‘country’ is to be formed from the southern Moreton Bay Islands, and the narrator, a young Aboriginal woman, takes a job as Cultural Liaison Officer to negotiate with a mysterious species of ‘plantpeople’ recently discovered living on the edges of the islands, ‘their green human-like heads lined up on the banks’.

Van Neerven explains she’s part of a growing number of Indigenous authors who are finding it productive to write in other genres, such as how Raymond Gates writes horror tales, Tristan Savage writes science fiction, or Siv Parker has created ‘tweetyarns’ on Twitter. She experiments with storytelling forms at every opportunity. As part of an event for the National Young Writers’ Festival, she stuck Post-it notes all over herself to present a ‘memory mashup’, mixing up random jottings and Facebook status updates, and afterwards asked the audience to do a ‘memory Mexican wave’ by sharing impromptu stories about their mums (many were in tears by the session’s end, as was van Neerven herself). She was surprised by the audience’s positive response, as she doesn’t feel she’s a natural performer: ‘I grew up in a family of amazing live storytellers, but I didn’t inherit the ability to tell a yarn. I’ve always been very private, and felt I could express myself better with pen and paper. When I dreamed about being a writer, I didn’t realise there would be so much performance involved.’

Van Neerven has Mununjali and Dutch heritage, and grew up in the same Brisbane neighbourhood where her mum was raised. Her mother, who belongs to the Yugambeh people of the Gold Coast and Scenic Rim, met her Dutch father while she was travelling in Europe, and they later moved back to Brisbane. Van Neerven admits she was writing stories in her journal from a young age (‘rip-offs of The Chronicles of Narnia’), but her main focus during her school years was sport. She attended a school with an excellence program in soccer, and still plays competitive soccer twice a week. ‘I’m definitely tortured and haunted by sport as much as I am by writing,’ she says. ‘Part of the problem is that I’ve never had any aggression in me, never been competitive enough. And I’m realising that writing is about competition too, not just actual awards, but making space for yourself to have a voice.’ It was in the confusion of finishing high school, unsure ‘what to do and who to be, never getting it quite right’, that she decided to study creative writing at Queensland University of Technology, with encouragement from her parents and extended family.

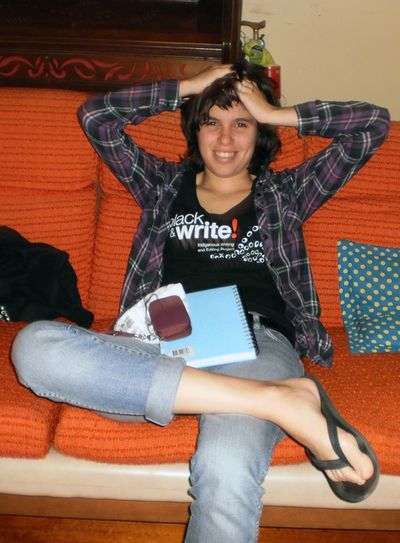

Van Neerven is now also an editor and mentor to other Indigenous authors as part of her work at the State Library of Queensland on black&write!, an Indigenous writing and editing project. She edited the recent digital publication Writing Black: New Indigenous Writing from Australia, and is currently editing work by Indigenous authors Jane Harrison and Adrian Stanley. For the moment, she is managing to balance writing and editing, though she feels ‘conflicted every day about what I should be doing with any energy I have, any creativity I have. When I was playing sport seriously, I knew how to prepare myself for a big match, but I’m still figuring out how to prepare to live and work well as a writer.’

Most of the stories in the book’s final section, ‘Light’, are set in the present, many told through the voice of a clear-eyed young female narrator who challenges fixed cultural and sexual identities. One of the recurring themes is how Indigenous identity has to be performed for outsiders, while at the same time proof of belonging is constantly negotiated within families and communities. A woman resents her estranged cousin when he asks for help with his Confirmation of Aboriginality application; she believes only those who ‘know who they are and … [are] living as who they are’ should be eligible, though she gradually accepts that full knowledge of self is an impossible ask of any human being. The cousin’s perspective is presented in another story about the childhood trauma that led him to leave behind that version of himself, why he had ‘stopped ticking the box’. As van Neerven says, ‘There is so much difference captured within this single identity. How can all the ways of belonging, of identifying as Aboriginal, ever be represented in one tickable box?’