I have spent quite a number of years reading about the enigmatic, engrossing historical figure of Joan of Arc, the young European peasant who ran away from home, became a knight, led the armies of the King of France against his enemies, and was burnt as a heretic in the early fifteenth century. Most historical accounts of the medieval woman’s life and persona are attempts at a purely factual representation of her story, or attempts at telling her story, as the thinker Walter Benjamin may have it (according to his important essay on the philosophy of history, as collected in Illuminations), ‘the way it really was’.

While some of these texts make for highly informative, persuasive historical studies and biographies of Joan – among my own favourites being anything by Régine Pernoud, Mary Gordon’s biography and Marina Warner’s brilliant study of Joan’s iconic image – they mostly confirm, supplement and contest the existing views of the famous figure, known to her contemporaries as Jehanne la Pucelle (Joan the Maid), rather than offering new depictions.

I am instead mostly interested in the portrayals of Joan that are, put in Benjamin’s terms, ‘our own concerns’. According to Benjamin, instead of focusing on ‘the way the past really was’, we must realise that ‘every image of the past that is not recognised by the present as one of its own concerns threatens to disappear irretrievably’. In other words, for a radical thinker or writer, the past is not over, but it is ‘time filled with the presence of the now’. Images of the past must ‘be blasted out of the continuum of history’ to be made new; in my view, it is creative writers and other artists, and not historians and biographers, who have provided us with a fascinating array of imaginative, unsettling, inspired and at times frankly weird new depictions of Joan of Arc.

Starting with her own contemporary, the late-medieval poet and feminist Christine de Pizan’s long poem La Ditié de Jehanne d’Arc (1429), poets, novelists, playwrights, composers, songwriters, painters and filmmakers have sought to remove Joan from her immediate historical and political context – that is, the battlefields of the Hundred Years’ War – to make her story relevant to literature readers, theatregoers and moviegoers of the artists’ own eras. In so doing, these artists have indeed blasted Joan out of her historical continuum, albeit with rather erratic levels of artistic success and effectiveness.

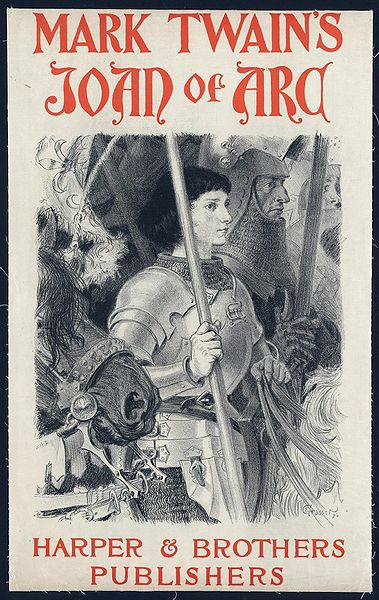

I find it fascinating that some of the least memorable literary depictions of Joan have been offered by some of the world’s best-known writers – such as Shakespeare, Voltaire, Schiller and Mark Twain – and many an acclaimed writer has failed to produce a version of the famous woman’s life that has stood the test of time. Thomas Keneally’s 1974 novel Blood Red, Sister Rose is one of the Booker Prize-winner’s least-known novels, and is currently out of print. Keneally’s decision to characterise his protagonist as some kind of gender outcast, due to her not menstruating, has very little historical basis – there exists only one second- or third-hand statement given by Joan’s (male) squire, Jean d’Aulon, 25 years after Joan’s death, in which the attendant claims to have heard that women who had seen Joan undress had not noticed signs of menstruation – but Keneally’s depiction is, nevertheless, unusual, even bold, speaking to the contemporary readers’ fascination with the body, gender, sexuality and physiology.

A far more successful and enduring modern retelling of Joan’s story is George Bernard Shaw’s 1923 play Saint Joan. While this text, as with most other creative representations of the historical figure, entails a level of loyalty to the historical records – most scenes in the play are based on rather well-known episodes in the commonly accepted narrative of Joan’s life, such as her supposedly miraculous recognition of the French King, Charles of Valois, upon her arrival at his castle in Chinon in 1430 – Shaw used the narrative to offer a new and timely critique of organised religion. In his version of the above historical scene, for example, Joan’s recognition of Charles is attributed to her common sense, intelligence and scepticism, and not the workings of a divine force.

Shaw’s humanist depiction of Joan may be seen as a reaction against her canonisation by the Vatican in 1920. Another powerful and arguably anti-religious portrayal of the medieval figure is to be found in a different work of this period, Carl Dreyer’s 1928 silent movie La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc. Here, Joan – portrayed by the actress Renée Jeanne ‘Maria’ Falconetti – is seen as a pious individual, victimised by the clergymen who intimidate and mock the young woman during her Trial of Condemnation, prior to sentencing her to death. Despite being a financial failure upon release, Dreyer’s film is now seen as one of the greatest movies of all time. Other cinematic depictions of Joan, however, have been far less compelling. The 1948 historical epic Joan of Arc with Ingrid Bergman, the 1994 two-part drama Jeanne la Pucelle with Sandrine Bonnaire, and 1999’s bloody, star-studded Jeanne d’Arc, featuring Milla Jovovich, have all been rather quickly forgotten. The latest movie based on Joan’s life, Jeanne Captive (2011), with Clémence Poésy, seems to have disappeared without a trace.

Joan of Arc’s historical narrative is perhaps too complex, paradoxical and challenging to lend itself easily to a literary or cinematic mould. But I don’t believe that readers interested in this remarkable figure should limit themselves to the works of historians and scholars. Creative writers and other artists have, in my view, mostly failed to produce depictions that do justice to the gravity of Joan; regardless, their work can be acknowledged as projects which have prevented the image of Joan of Arc from ‘disappearing irretrievably’. Even the epic rap battle between the Maid and Miley Cyrus on YouTube may help with animating the medieval figure ‘with the presence of the now’.