For a small country, Ireland has produced a significant volume of literature with widespread cultural impact. It continues to do so, counting among its successes six Booker Prize winners and four Nobel laureates. It doesn’t hurt that Irish writers are buoyed by an industry that really supports them, both financially – their government invests in literary culture the way ours invests in sport – and with a publishing industry that isn’t afraid to take risks.

With such a wealth of brilliant writers it can be overwhelming to know where to start. So here is just a sliver of possible recommendations to set you on your way through the vast literary landscape of the Emerald Isle.

On Irish identity

There’s no modern Irish literature without James Joyce, but if Ulysses feels too hefty a tome to tackle, start with Dubliners. Joyce’s collection of connected stories fuses experiments in style with realist portraits of regular folk, and pulses with a quiet nationalist fury from beginning to end.

Brooklyn is a lowkey, sensitive novel that works first on the heart and then engages the brain. Colm Tóibín’s tale of young Eilis Lacey leaving 1950s Ireland for a new, unknown life abroad, alone, is one of the best explorations the immigrant experience, especially on what it means to leave home and come back – what is changed and what remains.

The Colony is a story of England’s colonisation of Ireland, told in miniature. Audrey Magee’s cool, austere novel unfolds on a small, rocky island off the west coast of Ireland where the dwindling inhabitants clash with two deeply misguided outsiders – an English painter who has come to preserve what he sees, and a French linguist returning for his fifth summer to record the Irish language spoken there.

The Troubles and other troubles

Louise Kennedy’s debut novel Trespasses is set in Belfast 1975 at the height of the Troubles. The affair between Cushla, a young, compassionate Catholic school teacher, and Michael, an older, married, sympathetic Protestant barrister is the beating heart of this authentic and very affecting portrait of compromised lives in an occupied city.

In her second novel, Caoilinn Hughes traces the shattering effects of Ireland’s severe economic downturn. The Wild Laughter casts both an epic and intimate eye on a rural family pushed to the brink. The tragic human cost of recession gets the seriousness it deserves but also emerges with a humour that can only be described as black, and quintessentially Irish.

Alan Murrin’s debut novel, The Coast Road is set in an Ireland on the verge of legalising divorce; that’s a day that can’t come too soon for the three women whose lives intersect here. Murrin has that rare gift – the ability to write multidimensional characters who lift right off the page, rendering their struggles beautifully and painfully real.

Family dramas

Claire Keegan’s compact fiction contains everything that is decent about human beings while not shying away from the wrongs we so often do each other. That Foster – a delicate and very moving story of a lonely young girl’s summer living with foster parents – manages to contain so much of the human experience across only 96 pages is something close to a miracle.

Families are the centre of Anne Enright’s fictional universe and I have a soft spot for the personal struggles of the four Madigan siblings who live within the pages of The Green Road. Enright’s structure is clever and controlled, moving her characters across nearly thirty years as they leave the family home then return to it for one final Christmas.

Not enough people know who John McGahern is – simply, one of Ireland’s greatest novelists, a writer of tremendous restraint and rare insights. His masterpiece, Amongst Women, first published in 1990, features a veteran of the Irish War of Independence whose mid-century disillusionment with the status of the Republic he fought for infects every member of his family.

Mastery of language

Set during the American Civil War and Indian Wars, Sebastian Barry’s seventh novel, Days Without End, is narrated by the orphan Thomas McNulty, an emigrant from Ireland’s Great Famine, who as a teenager first befriends the American John Cole and then falls in love with him. Barry wrings moments of grace and intimacy from the violent, chaotic tapestry of history with visceral, lyrical prose. Sentence for sentence, this is probably the most breathtakingly beautiful book I’ve ever read.

John Banville won the Booker Prize for The Sea, which joins aging art critic Max Morden on his return to the seaside town he grew up in, in the days after his wife’s death. Mixing memory and desire, Max revisits childhood memories, the lead up to Anna dying, and his current situation. The great Seamus Heaney remarked: “isn’t it wonderful to be part of a culture that produces prose as good as that?”

Last year’s Booker Prize win for Prophet Song confirmed Paul Lynch as one of Ireland’s best, but his earlier novel, Grace, which follows a teenage girl and her brother as they journey across an Ireland on the brink of famine, had already established the singularity of his voice. Here Lynch finds exuberant poetry amidst the suffering – the beauty of the language skilfully magnifying the black horrors it’s being used to describe.

Experiments in prose

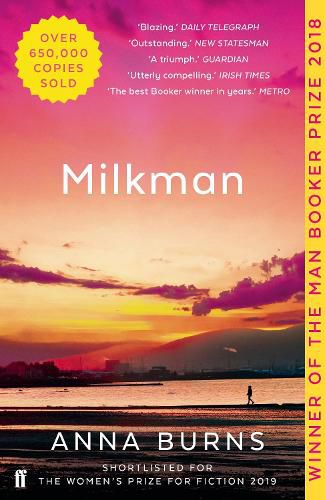

In an unnamed town in 1970s Northern Ireland, the narrator of Anna Burns’s Booker prize winner Milkman is known only as ‘middle sister.’ She’s a darkly funny narrator, eighteen with a ‘maybe-boyfriend’ but also the subject of unsettling and unwanted attention from a dangerous paramilitary officer referred to as ‘milkman.’ Hers is a unique voice: rambling yet coherent, increasing the claustrophobic tension of the powder keg environment she’s living in.

Eimear McBride’s debut novel, A Girl is a Half-formed Thing, is a stream of consciousness narrative cleaved from deep inside its narrator, a young woman traumatized by a past sexual experience and other family troubles. Breaking all the rules of storytelling, style and punctuation, this is a book on fire with originality, taking small shards of visceral truth and turning them into a stunning whole. Worthy of what Anne Enright called “instant classic” status.

Coming of age

I love The Country Girls Trilogy by Edna O’Brien, a three-part novel first published in the 1960s and swiftly banned by the Irish censor for its sexual content. What was most ‘offensive’ however was that it represented the truth about being a woman in postwar Ireland. Childhood friends, Kate and Baba, follow a path less travelled into adulthood, pursuing pleasure and making choices outside the expected. O’Brien uses lyrical prose and a Joycean attention to detail to criticise a country where every aspect of women’s lives gets stifled and scrutinised by Church and state.

Roddy Doyle won the Booker for Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha, his 1993 coming-of-age novel about a ten-year-old boy that, as the title suggests, is told with great humour. But there’s loads of pathos too, as over the course of approximately one year, Paddy Clarke’s life becomes gradually tougher. Doyle is a great storyteller, and his book brims with vivid details of Dublin life in the late 1960s, alongside a very personal portrait of the boy becoming a young man.

Acts of Desperation, the debut novel from Megan Nolan, features a narrator retracing the torrid terrain of a toxic relationship she had in her early 20s. Like the work of Sally Rooney, power dynamics are at the fore here, but Nolan’s book is a far darker beast, fearless in its narrator’s self-excoriation of her obsessive desires in the face of such a cruel, ungiving love. Honest, raw stuff.