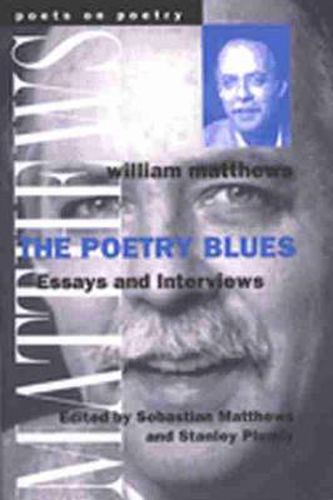

The Poetry Blues: Essays and Interviews

William Matthews

The Poetry Blues: Essays and Interviews

William Matthews

The amnesia that surrounds our earliest life is not only a great human mystery but also a receptacle into which is poured by the baby’s relatives the beginnings of a life story. In later years these relatives can look at the grown child and see their first observations confirmed, for was he not always a curious baby, a cranky baby, a calm baby, what have you? We come into the world swaddled in the beginnings of a story, and, by the time we begin remembering and tending it, it already has a shape and a momentum. When I was born, in 1942, my young parents were following my father’s naval orders around the country–Bremerton, Washington; Norman, Oklahoma. I spent many of my first months with my father’s parents in Cincinnati. There are photographs of me in, of course, a sailor suit. The lawn at the back, or western side, of my grandparent’s house had a few huge trees–could they have been oaks?–and I think I remember standing at the edge of that lawn, on a kind of flagstone patio, in the late-afternoon light, staring excitedly and contentedly at the effect the tall trees and their long shadows made. The world seemed vast and full of comfortable mystery, and yet I was but a few feet from the safety of the house. But that would have, of course, been later, when I was four or maybe even six. I stood there often. And, of course, I’ve seen photographs of the lawn and house. And maybe I’m recalling some older relative’s anecdote about a boy at the edge of a lawn that somehow, inexplicably, has got blended into my own memories, like vodka slipped into a bowl of punch. My earliest memory seems to be from the back yard of my mother’s mother’s house in Ames, Iowa. There’s a sandbox, a tiny swatch of grainy sidewalk, and–there! it’s moving–a ladybug. I have tried again and again to construct a tiny narrative from these bright props, but they won’t connect. They lie there and gleam with promise but won’t connect. \ls\ The war ended, my sister Susan was born, my father took a job with the Soil Conservation Service in Ohio, and then the four of us were in a boxy farmhouse outside Rosewood, Ohio, for a year and then moved into a house just outside the city limits of Troy, Ohio. The smells of that house, that life, those years, I absorbed all unthinkingly, as greedily and easily as breath. Later, thinking back fondly on them, I at first organized them easily: indoors and outdoors, female and male. Coffee, dishwashing liquid, baking are foremost among the kitchen smells, and the braided scent of misty heat and faint scorch that meant ironing. I remember, too, coming home from school during the Army-McCarthy hearings to find my mother ironing glumly, fascinated and appalled by what I now know to call the self-righteousness and swagger and mendacity of the whole gloomy circus. Once or twice–I think I remember this correctly–she was weeping a little. A child’s world is small. Think how easily I wrote the war ended earlier. I don’t remember it myself. In 1945 I remember I suddenly had a sister. I saw in the kitchen those puzzling afternoons how the cruelty of the official world, the world that history records and by whose accounts I knew to write that the war ended, could come into the house and linger, itself a sort of odor.

This item is not currently in-stock. It can be ordered online and is expected to ship in approx 4 weeks

Our stock data is updated periodically, and availability may change throughout the day for in-demand items. Please call the relevant shop for the most current stock information. Prices are subject to change without notice.

Sign in or become a Readings Member to add this title to a wishlist.