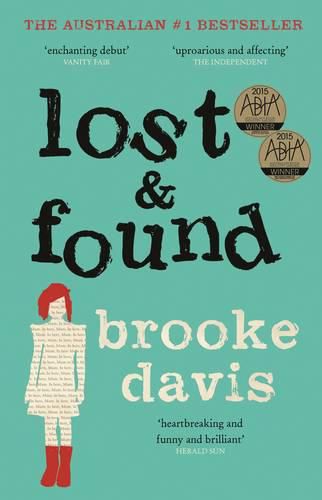

The story of my book: Lost & Found

It’s May 2013. I’m sitting in a café in Nova Scotia, Canada, checking my emails, sipping on a cup of tea. My two brothers are there, too. We haven’t seen each other for a while, and they’re talking about music again. I can never keep up when they do this. Every band they mention is so obscure it sounds as if they’re making them up on the spot.

Their conversation goes something like this**:

‘Have you heard Candleface’s new album?’

‘Nah.’

‘It’s wicked.’

‘I’m not into that gravelpit rock-sock scene as much as you are. You listened to that Scissorpen tune yet?’

‘They remind me so much of Heads of Frink.’

‘I know. Bit more alt-prog-stargaze-noodle, though.’

‘Yeah.’

‘Yeah.’

And then I say: ‘Hey. I just got this crazy email.’

‘Yeah?’ one of them says.

‘Yeah,’ I reply. ‘It’s from the guy who said he’d take Lost & Found to that publisher’s head office for me? It says: “Um, I don’t want to get your hopes up, but Vanessa from Hachette just rang me on a Sunday and said: Todd, if I don’t get to publish this book, I’ll cry.” ’‘That’s pretty cool,’ one brother says.

‘Yeah,’ says the other.

‘Yeah,’ I say.

There’s no jumping around or anything. They continue their inaccessible conversation, and I read the email again, and continue to sip my tea. The next week, I say goodbye to my brothers and head to St John’s, Newfoundland, where I end up negotiating the terms for the publishing contract with Hachette. I do it via pay phone on a blustery harbour in the dark hours of an early morning or two, straining to hear my agent’s voice as late night revellers try to join in. One morning, I receive an email declaring that everything is finalised, that Lost & Found will actually be published, as a book, A REAL BOOK, not one that Officeworks did for me, or one hand-written and illustrated by myself on cardboard, like those I made in Primary School.

That evening, I hike up Signal Hill, a steady incline that rises up around the outskirts of St John’s and guards its port entrance. There’s a view of the never-ending ocean on one side, and the brightly-coloured city on the other. I find a spot and sit there for a long time. I breathe in, and breathe out, listening to the boats glide through the water, watching the sun disappear into the landscape. I think: I want to remember everything about right now.

Then, a tour group full of mature age travellers gathers nearby, and, just as the tour guide begins to wax lyrical about the historical significance of the site, an elderly woman farts, loudly, and the entire group politely pretends that nothing has happened.

And I think: Especially that.

I hike back down, the air feeling tight and real and sharp. I find a bar, and sit there, drinking wine, reading a book with a dumb smile of my face, blissfully lost in thoughts of book deals and farting women. A local approaches me, eyeing my book and the wine, and says, ‘You’re not from around here, are you?’ Her and her friends are the first people to know my news – they shout me celebratory drinks for the rest of the night, and we become friends.

Photograph by Ailsa Bowyer

I don’t tell anyone back home for two whole days – not even my brothers – and it feels powerful, and gorgeous, to keep such news to myself, just for a little bit.

It’s May 2014. My brothers are now actually excited about the whole thing, in that way only siblings can be, because they’re you-but-not-you. I meet my younger brother for coffee on St Kilda Road in Melbourne and hand him an advanced copy of Lost & Found.

‘It’s yours,’ I say. He looks at me, eyes a little wider than usual, then turns it over in his hands as if it’s evidence that God exists. I can’t help smiling, and I think: I want to remember everything about right now. And then he starts to dance in the street with it, thrusting the book sideways and up and down and over his head, hopping from one foot to the other, and singing, not terribly quietly,

‘This is my sister’s booo-oook, this is my sister’s booo-oook.’

And I think: Especially that.

** It was not at all like this.