Alison Croggon talks about the process of writing her new Young Adult novel,

It’s hard to know when a book begins. Perhaps Black Spring began when I was six years old and running over the bone-strewn turf of the Cornish moors with my sisters. I remember the boundless feeling of freedom: I loved the wind rushing over the bare hills, the granite tors that thrust out of the ground. The moors were my favourite place in the world then. Or maybe it began when I first read Wuthering Heights in my early 20s, and thought idly: I’d like to write a book like that one day. Or maybe it was in my early teens, when I first read Emily Brontë’s poetry.

Maybe a novel begins when you write the first words. I am good at starting novels: I have around five unfinished works on my computer, some quite substantial. Some of them end up being written, some of them don’t. They always begin with an image, or a feeling, or a voice or a thought. I follow this along for as long as it seems to last, and then I usually run out of ideas. I put it aside and wait to see if it is actually alive.

Black Spring began like that. I wrote the first part a long time ago. I’m not quite sure when. I was thinking about the story-within-a-story structure of Wuthering Heights; that Chinese box quality is one of the things that attracts me about the book, and I thought I would like to put that to use in a fantasy novel. One of the things I like about that structure is that it’s all first person, but you are not limited to the knowledge of a single character. In fact, in Black Spring, there are three first-person narratives, all of them telling different aspects of the same story.

When I started writing Black Spring, it had been several years since I had read Wuthering Heights. I am not interested in writing pastiche; I wanted to write a book that paid tribute to Brontë but that had its own autonomy and freedom as a story. I find that freedom in fantasy: it allows me to make my own world, with its own metaphors and laws.

But I needed another element to throw into the crucible. Some years ago I read Ismail Kadare’s novella Broken April, a fictional account of the vendettas in Northern Albania. It was this book that sparked the world alive for me: I stole the geography and many of the laws, and added magic.

One day I thought of a narrator called Hammel, who like Brontë’s character, Mr Lockwood, rents a house in the wilds, goes to visit his landlord and has an alarming experience. Hammel is a writer, a poet, who I rather wickedly enjoyed writing: he’s full of his own self importance, deeply sexist and rather timid. Hammel recounts why he is visiting the Northern Plateau, and how he got there, and describes the world in which he lives. It’s a 19th century sort of world, complex and corrupt. He lives in a nameless country that is remote from the imperial centres of civilisation: a small kingdom that’s a kind of petty province. What’s important is that it is divided into two regions: the urban, sophisticated south and the rural, wild Northern Plateau.

I’m the sort of writer who tends to discover the world I’m making up as I write it, and at that point, that was all there was. I left Hammel alone for maybe a year, or more. I can’t quite remember. I was writing other things, including a novel that I have just finished called Simbala’s Book, and I didn’t have a clue where the book might move next. I thought sometimes that I would have to abandon it, that it was one of those ideas that never bear fruit. And there things more or less stayed until I went to England, on a poetry reading tour I was awarded by Poetry Australia, in 2009.

Halfway through the tour, I was given a residency at the Wordsworth Trust. I was staying in Grasmere, in the middle of the Lake District. I had a whole week in which I could do whatever I liked, which is a rare luxury in my life. Aside from a couple of reading commitments I was left to my own devices. I was put up in a beautiful lodge, an old house not far from the village, with wooden shutters on the windows. I was supposed to be writing poetry, but instead, guiltily, I pulled out Black Spring. It was autumn, and the leaves were turning. Perhaps it was the misty tors, the fact that it rained every day, my morning walks past damp sheep, the constantly changing colours of the hills: whatever it was, I ended up working on Black Spring.

Most importantly, I finally could hear the voice of my second narrator, Anna. I can’t write a book unless I hear its tone and diction; it needn’t be a character’s voice, but in this case, it was the characters I needed to hear. I finished the book after I returned home, over the next five months.

I didn’t read Wuthering Heights while I was writing Black Spring, except on a couple of occasions when I allude to particular passages. I wanted them to rhyme with Brontë’s, so that they consciously echoed what she wrote but had very different, sometimes opposite meanings; so I would just find that particular passage and read it very closely. Black Spring is, in many ways, a love letter to Emily Brontë. I even included some lines from reviews of Wuthering Heights that came out when it was first released, but that was just for my own fun. I like to think that somewhere Brontë is chuckling sardonically.

For half of it, I really enjoyed writing it. When things went bad, as they were always going to in a book like this, it became more difficult. I remember that, as the novel reached its climax, I worked out that I probably had a month’s worth of writing to do. And then I wondered how on earth I was going to last a month in that emotional place, while at the same time knowing it was too late to abandon the book, that now I had to finish it.

It sounds ridiculous, and I often think it is ridiculous; but I suppose that when you write a fiction, you have to imagine what it is your characters are feeling as well as thinking. You have to be at once inside them and outside them. And with this book, I really had to grit my teeth to finish it. It’s a book about extreme emotions, extreme people. Anna, my major narrator, is probably the only really sane character in the book. I found her a joy and relief after the passions of my other characters. Also, among other things, it’s a book about woman-hatred and injustice, and in order to write about those things, you have to go there, you have to pull on things you know inside yourself that maybe you’d rather not know.

But all that was a long time ago now. The real pleasure happens when you actually hold the book in your hands. I always feel a faint astonishment, as if I can’t quite believe that I wrote it. But there it is.

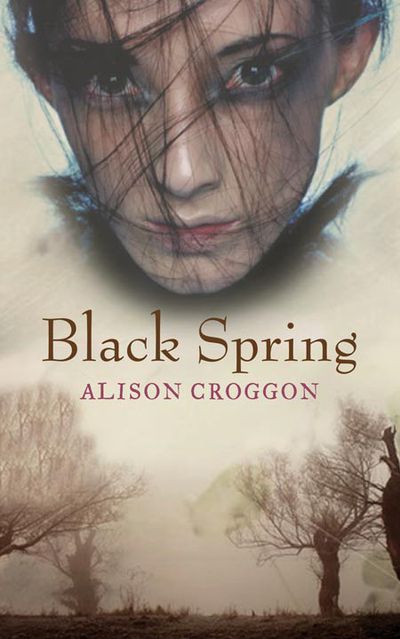

Black Spring