Majok Tulba arrived in Australia from Sudan in 2001, having narrowly missed out on being recruited as a child solder for a rebel army. Alice Pung talks to him about his debut novel,

When Susan Sontag wrote Regarding the Pain of Others, about portraying hell through art, she said that this portrayal was not intended ‘to tell us anything about how to extract people from that hell, how to moderate hell’s flames’. Portraying hell does not mean the portrayal will make things good. Yet Sontag recognises that it seems a good in itself to acknowledge how much of our human suffering is caused by human wickedness.

Majok Tulba’s Beneath the Darkening Sky is about such human cruelty, told through the voice of a child. What is striking about this powerful book is that there is no over-arching framework of morality as we would understand here – only survival through eternal vigilance. ‘You had to be aware of danger and we were confronted by death and evil in our world and this was desensitising,’ explains Majok. Much of this story is about the rapid loss of a short-lived innocence, an innocence paralleled with the author’s recollections of his childhood:

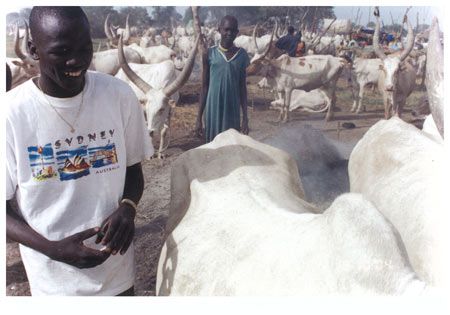

‘My village was a paradise. As a boy, I loved staying outdoors; tending goats, hunting in the woods and playing with my friends in the fields. Mornings were the best. It was my favorite time of day, that morning light, it made the greens on the hills so much greener and the sky was always that perfect blue.‘

Born and raised in Pacong, a village by the waters of the White Nile in Southern Sudan, Majok was once measured against the length of an AK-47 rifle – the height test used by a marauding army for recruiting boy soldiers – and fortunately fell short. However, he lived through a country that was in the maelstrom of a civil war. This is how he came to be able to write about Obinna, a boy whose Nigerian name means ‘Strong Hearted’, and Obinna’s attempts to stay alive through luck and prudence. Yet his is a luck that is truly vagarious, and a prudence that relies on animal instincts.

Beneath the Darkening Sky is a work of fiction, not autobiography, but Majok says that every child in Sudan would have seen many of the things he has written about: ‘There are far more vivid images I have seen, and I had to scale back the reality of much that occurs there, because the Western reader would be appalled.’

It is interesting that Majok refers to the ‘Western reader’. Although this reference is not one of contempt but respect for sensibilities that have not been exposed to the sheer banality of brutality, Majok has understood that some of the things he has witnessed in his life seem too atrocious to be credulous – though real they are.

Perhaps fiction from a first-person perspective offers a way to portray that truth without opening up personal traumas, and to avoid too many probing questions about his own experience. It is also a good way to prevent being heralded as a personal ambassador for political or social commentary, or representation of a diverse ethnic group. Obinna’s story is his own, and the fictional gap enriches it, gives it room to inhale and exhale before beginning to document the lives of the South Sudanese.

And document it he does. The visceral descriptions of looting, pillaging, rape, amputation, massacre and depraved violence which occur throughout two thirds of this book could seem unrelenting, but for the narrator’s convincing humour and adolescent awkwardness – amazingly enough, Obinna is a wry and funny storyteller, even in the midst of getting beaten up. The misogyny of the soldiers is documented with no overriding redemption, and the steady slide into a universe of the hunter and the hunted appears inevitable considering the psychological torments to which the boys are subject.

You cannot see a war through a filter, you cannot look at darkness through rose-coloured glasses because all you get is the colour of clotted blood. I understand this from my own family experience as a child of a genocide-survivor; Majok has written about war in a way that does not glorify anything. He has the unflinching simplicity of Primo Levi, set in a world of heat and not cold. If Levi wrote If This Is a Man, then Majok has written a story that could very well be alternately titled If This Is a Boy – there are none of the ‘childhood’ traits we would like to superimpose on his children characters, particularly not innocence.

Living in Sydney since 2001, Majok came to Australia as a refugee, and also works as a filmmaker. Interestingly enough, the novel reads like a finely crafted film script, so vivid were its descriptions and settings. As a director though, his hand is unwavering. In Sudan, storytelling is not based on the written word.

‘My family have no idea that stories can be told in a medium other than oral, and oral storytelling is unpaid job in my country,’ Majok states. ‘My family want me to work in the bank or become a doctor. A writer is an unknown career in Southern Sudan. The other jobs would give high status in the community, whereas as a storyteller is a fun, passing the time activity with no pay and no status.’

Yet this is not a ‘fun’ book. It is an adventurous story, a daring one, a necessary tale to tell. Unlike Dave Eggers’s What is the What, another vivid and compelling narrative about a boy soldier, Majok’s story does not extend to arrival in a new country – it is set firmly in the war zone. However, Majok is focused on bridging an understanding between the newly arrived African refugee communities and the wider one. He believes that there is very little positive representation of Sudanese in Australian mainstream media, and that many of the problems reported are due to a lack of insight into ‘refugee trauma reactions and the psychological impact of past experience on the present’.

There are novels that bore into a reader’s psyche long after the last page, leaving behind a residual smear of dark feelings. Yet dark does not necessarily mean bad – you do not feel, while reading the story, a sense of inchoate despair. It is more terrible to not acknowledge that such darkness exists. Sontag warns against this type of willful blindness in Regarding the Pain of Others):

‘Someone who is perennially surprised that depravity exists, who continues to feel disillusioned (even incredulous) when confronted with evidence of what humans are capable of inflicting in the way of gruesome, hands-on cruelties upon other humans, has not reached moral or psychological adulthood.’

Beneath the Darkening Sky is a devastating book, but after reading it, it is not a book that leaves a reader feeling devastated. It is a book about growing up that leaves us clearer about what to feel regarding the pain of others, with an understanding about how human beings can regenerate, slowly. As Majok concludes during our interview:

‘I don’t want to change the world but I look forward to the day when humankind awakes and sees the world as it is, a beautiful place.’

Beneath the Darkening Sky

Alice Pung’s latest book is