Readings Newsletter

Become a Readings Member to make your shopping experience even easier.

Sign in or sign up for free!

You’re not far away from qualifying for FREE standard shipping within Australia

You’ve qualified for FREE standard shipping within Australia

The cart is loading…

This title is printed to order. This book may have been self-published. If so, we cannot guarantee the quality of the content. In the main most books will have gone through the editing process however some may not. We therefore suggest that you be aware of this before ordering this book. If in doubt check either the author or publisher’s details as we are unable to accept any returns unless they are faulty. Please contact us if you have any questions.

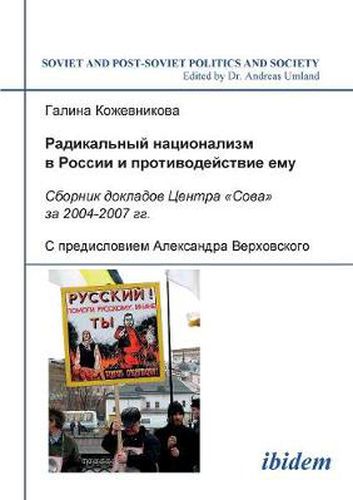

By the end of the 1990s, the general subject of nationalism in Russia became largely identical with the narrower theme of ethnic Russian nationalism. At the same time, within the latter phenomenon, there happened some significant changes as compared to the 1990s. Since the turn of the century, an increasingly stable ethno-xenophobic majority has been taking shape, and been courted by various members of the political class. Different kinds of party leaders and representatives of the government, from the minor bureaucrat up to the President, have started to actively use negative ethnic stereotypes and exploit xenophobic attitudes among the Russian population. In the radical nationalist movement, the Skinhead element has gained prominence. Concurrently, racist violence has increased spreading to the majority of Russia’s regions. Moreover, the neo-Nazi youth movement, while remaining relatively independent and unorganized, has attracted the attention of ultra-right ideologists. Today, many established ultra-nationalist organizations are linked, in one way or another, to Nazi Skin-groups.In view of these developments, currently topical aspects of the rise of Russian nationalism are: the dynamics of public expressions of ethnic or/and religious xenophobia; the functioning of informal structures within the nationalist movement; the ways nationalists appeal to the population at large; and the reactions of the state and non-nationalist parts of civil society to these challenges. To one degree or another, these themes are the topics of the reports of Moscow’s Sova [Owl] Information and Research Center collected in this Russian-language volume.Contents: Autumn 2004: An Explosion of Xenophobia in Russia - an Invention of the Media or Reality?; Winter 2004-2005: Antisemitism, Skinheads, et cetera; Spring 2005: Xenophobia in the Minds and on the Streets; Summer 2005: Skinheads Take no Holidays; Autumn 2005: Marching on Corpses; Winter 2005-2006: Racists Are Scared by neither the Cold, nor United Russia; Spring 2006: A Skinhead Promotional Campaign; Summer 2006: An Anti-Extremist Season - the Skinheads Attack and the State Duma Reacts; Autumn 2006: Under the Signs of Kondopoga; Winter 2006-2007: Maneuvers of the Ultra-Right - Explosions, Congresses and Trials.

$9.00 standard shipping within Australia

FREE standard shipping within Australia for orders over $100.00

Express & International shipping calculated at checkout

This title is printed to order. This book may have been self-published. If so, we cannot guarantee the quality of the content. In the main most books will have gone through the editing process however some may not. We therefore suggest that you be aware of this before ordering this book. If in doubt check either the author or publisher’s details as we are unable to accept any returns unless they are faulty. Please contact us if you have any questions.

By the end of the 1990s, the general subject of nationalism in Russia became largely identical with the narrower theme of ethnic Russian nationalism. At the same time, within the latter phenomenon, there happened some significant changes as compared to the 1990s. Since the turn of the century, an increasingly stable ethno-xenophobic majority has been taking shape, and been courted by various members of the political class. Different kinds of party leaders and representatives of the government, from the minor bureaucrat up to the President, have started to actively use negative ethnic stereotypes and exploit xenophobic attitudes among the Russian population. In the radical nationalist movement, the Skinhead element has gained prominence. Concurrently, racist violence has increased spreading to the majority of Russia’s regions. Moreover, the neo-Nazi youth movement, while remaining relatively independent and unorganized, has attracted the attention of ultra-right ideologists. Today, many established ultra-nationalist organizations are linked, in one way or another, to Nazi Skin-groups.In view of these developments, currently topical aspects of the rise of Russian nationalism are: the dynamics of public expressions of ethnic or/and religious xenophobia; the functioning of informal structures within the nationalist movement; the ways nationalists appeal to the population at large; and the reactions of the state and non-nationalist parts of civil society to these challenges. To one degree or another, these themes are the topics of the reports of Moscow’s Sova [Owl] Information and Research Center collected in this Russian-language volume.Contents: Autumn 2004: An Explosion of Xenophobia in Russia - an Invention of the Media or Reality?; Winter 2004-2005: Antisemitism, Skinheads, et cetera; Spring 2005: Xenophobia in the Minds and on the Streets; Summer 2005: Skinheads Take no Holidays; Autumn 2005: Marching on Corpses; Winter 2005-2006: Racists Are Scared by neither the Cold, nor United Russia; Spring 2006: A Skinhead Promotional Campaign; Summer 2006: An Anti-Extremist Season - the Skinheads Attack and the State Duma Reacts; Autumn 2006: Under the Signs of Kondopoga; Winter 2006-2007: Maneuvers of the Ultra-Right - Explosions, Congresses and Trials.