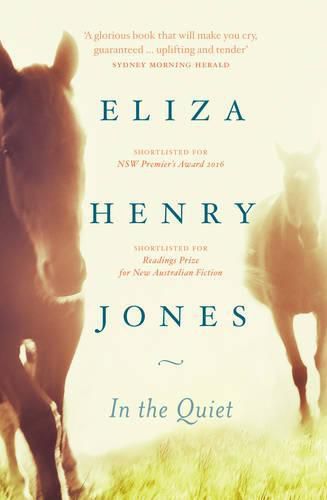

Read an excerpt from In the Quiet by Eliza Henry-Jones

In the Quiet is the debut novel from Australian author Eliza Henry-Jones. Here is an extract from the book.

I don’t know how I died. That’s strange, isn’t it? To be dead and know that but to not know how it happened. To not know my last memory.

It’s not something that I ever considered when I was alive.

I can see and I can hear. And when I remember back to other times and other places, I see and hear them as though I’m reliving them.

But when I remember, I miss things that are happening now. I miss chunks of time. I try not to remember. I try not to think. I watch and I listen and I hope to not miss any more time. Because time is all I have now. And how quickly it disappears.

*

The first thing I am conscious of is my little girl, Jessa. She’s sitting on the verandah wearing the blue dress I bought her last summer. She has, perhaps, worn it twice since then. She is coming into her teenage years and the dress already seems too short, riding high above her knees. She’s fiddling with a nail from a horseshoe and keeps stamping her foot.

There’s bull ants. That’s why.

She stares left, where the big paddock is. She makes a clucking noise with her tongue, like she’s coming in to a jump on her pony.

Purple flowers from the jacaranda start to fall and she shakes her head free of them and glares up. ‘Don’t,’ she says.

And above her head Rafferty is hanging out a window, grinning, one hand wrenching a branch backwards and forwards.

‘I said don’t!’

She is on her feet, fist clenched around the horseshoe nail. She runs inside, straight into her father.

‘Whoa,’ he says, patting her. ‘Easy.’

*

My husband, Bass – Sebastian – is a farm boy. He has always been prone to stroke me and make cooing noises whenever I was unhappy or unsettled. Has been prone to make clucking noises, like Jessa, if I walk too slowly down the street. When he is impatient or bored, he will blow his breath out in a raspberry that sounds like a relaxed Clydesdale.

Sometimes I sense he wants to give me a good kick, like he would when riding a stubborn horse.

I miss his hands. The warmth of them.

If I could still feel, I’m sure the yearning for them would be enough to make me ache.

*

My boys are sitting in their room. It is dark now. But it must be warm outside because they have the window open.

Rafferty is sitting on the sill, near the top of the jacaranda tree. He is smoking. His boxers have a hole in the side and the T-shirt he’s wearing is stretched out and faded.In the night sky, the stars are out. And there’s a haze around the moon.

‘Put it out,’ Cameron says. He is in bed with the blankets pulled up, nearly to his neck. Rafferty turns to glance at him and takes another long drag. The tip lights up and he blows smoke rings out into the still night. It is strange, to see him smoking. Strange to see him so adult. Altered, but the same.

‘Please?’ Cameron says.

Rafferty sighs as though Cameron has just asked him to cut off a leg, but he slowly butts it out on the sill. He slaps at a mosquito and sighs.

‘Thanks.’

Rafferty grunts and lies on his bed. His doona is kicked off the end, but he doesn’t make a move to grab it. He puts his hands behind his head and stares up at the ceiling, where the moon has fanned shadows of the jacaranda branches. Rafferty blinks slowly, watching their stillness.

‘Are you okay?’ Cameron’s voice is quiet. Barely a whisper.

‘Of course I am.’

*

The twins came suddenly and violently at the end of spring. Afterwards, wet with blood and nauseous and trying not to cry, I stared down at two sets of eyes. They were blue when they were born, but as they grew their eyes turned an extraordinary shade of hazel. They made me think of stones in a river, lit up by the sun through water.

Bass’s eyes.

They spent their first few months in nappies and singlets. When they were older I let them crawl around the verandah naked, and when I took them inside at dusk, Bass hosed the wood clean.

Those evenings smelt of earth and milk.

*

It is just before dawn. The same night, I think. Cameron has thrown off his blankets and is sprawled so that one foot is nearly touching the ground. I had been looking at double beds for them, before. But Bass seems to have forgotten in the after. On the other side of the room Rafferty has curled up in a ball, his head underneath his pillow, his arms curled around his stomach.

He says it so quietly, I barely catch it.

‘Mum,’ Rafferty whispers, his eyes pressed shut.

*

Sometimes I try to remember back to what happened. I often do this at night, when they’re asleep. My family. But it’s rare for all four of them to sleep through the night. Cameron twitches himself awake at about midnight and does the breathing exercises the school counsellor taught him in year seven. Rafferty will often wake up at the same time and sit at the window and smoke.

Jessa wakes biting back a cry. The noise comes out as a hiss. She will lie in bed with her lips pursed, when this happens. I don’t know for how long. Then she will sigh, as though she is disappointed in herself, and tramp down the hall and into our bedroom.

Bass’s bedroom, now.

As often as not he will be in the kitchen when she comes looking for him. Sometimes drinking Scotch and other times drinking warm milk with a little cinnamon. It’s what I make, what I made, for the boys and Jessa when they had nightmares or couldn’t sleep.

Jessa and Bass will curl up in bed. Bass on my side. Jessa on his. They fall asleep back to back and always wake up holding hands. They sleep with the blankets kicked off and the portable fan in the corner of the room on high.

Nearly every night these things play out.

And nobody ever speaks.

*

In so many ways, the house has moved on without me. Beyond me. But some things remain unchanged. As if they are stalled. As if time has stalled without me.

There is fresh, mismatched bedding on Bass’s bed. Flannelette and cotton, blue-grey and orange. He has left my pillowcase on. The blue and white patterns of it. He sleeps on it every night. It must smell more like him now than it ever did of me.

Jessa chips the nail polish off all her fingers but leaves it on her toes. It’s nearly grown out, just little flecks left on her big toes. Blue nail polish. I’d put it on for her, to cheer her up over a miserable day at school.

The jar of nail polish is still on the coffee table. I want Jessa to unscrew the lid. I want her to paint her nails. I want the boys or maybe my sister, Bea, to paint the nails on her right hand, her dominant hand.

A few of the same towels are still hung in the bathroom. They have been in there for weeks, maybe months. I don’t think anyone is using them, but nobody is washing them clean, either.

The radio is tuned to the golden oldies station I liked to listen to. The sound of it. It makes the world soften. It reminds me of my eyes blurring with tears.

The roses I picked from the garden and set on the sideboard in the living room have lost their colour, are rotting in water that is now mostly green. Their petals are papery and brown, under lounge chairs and puffed down the hallway and into other rooms. There are other flowers, set into corners and on tables. Flowers I haven’t seen before. Dying flowers, some with cards still attached. On shelves and in dirty vases on the verandah.

There is dog hair, dust. Collecting in nests under the couches and chairs and tables. I wonder if it smells dusty, inside. Smells as stale as it looks.

Outside, the property is yellowed and browned from summer. The only green is in the beds immediately around the house. Even the leaves on the eucalypts, the silver stringybarks and lemon scented, are dulled from the heat and the dust.

A pang, like something metallic pressed against the tongue. I want them to move, one way or another. I want them to throw out the roses. I want them to vacuum. I want them to wash every piece of bedding, every piece of tearstained clothing. Blue nail polish. A tended garden. I want them to move. Be moving.

Secateurs left near the rose beds. There are clothes turning damp in the dryer.