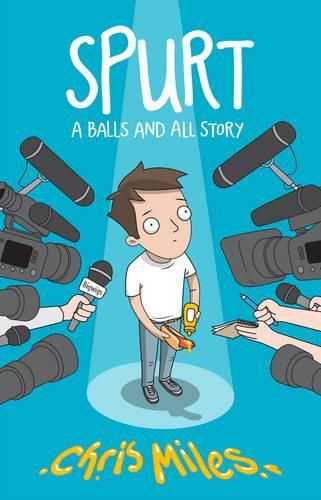

Inflatable boobs and other awkward moments in young adult fiction

Young adult author Chris Miles tells us why you should be embarrassed to read young adult – but not in the way you think…

Cringe comedy has become a TV staple courtesy of sitcoms like The Larry Sanders Show, The Office and Curb Your Enthusiasm. But it’s been a staple of young adult fiction since at least as far back as the 1970s, when Judy Blume published Are you there God? It’s me, Margaret. Awkward moments abound: Margaret’s first bra-fitting, taking her first box of sanitary pads to the drugstore counter only to have it wrapped by a boy, and the shock discovery that her friend Nancy has been lying about having her period.

The comedy of awkwardness, embarrassment and humiliation is a natural fit for YA literature. Characters in this kind of comedy are frequently driven by status anxiety – and for young adults, status anxiety is acute and unremitting. It’s a mode of comedy that ruthlessly exploits the gap between the way we’d like to be seen, and the way we actually are. Teenagers want to be seen as being adult and mature, in a world that still wants to treat them like children. When Adrian Mole tries to reinvent himself by painting over the Toyland wallpaper in his bedroom, he is cruelly thwarted when, even after three coats of black paint and numerous applications of felt tip pen, Noddy and his ‘bloody hat bells’ refuse to stay concealed. Likewise, when Siggy in Doug MacLeod’s Siggy and Amber gets drunk on whisky for the first time at the youth club disco and attempts to chat up the purple-haired girl with whom he has instantly fallen in love, he is, by the will and decree of the cringe comedy gods, absolutely destined to vomit on her shoes.

Characters like Adrian Mole and Margaret Simon and her friends flirt with doom when they try to pass themselves off as something they’re not. But in an interesting inversion of the embarrassment trope, Candice Phee in Barry Jonsberg’s My Life as an Alphabet has her life saved, not ruined, when she’s rescued from drowning by the inflatable fake breasts she happens to be wearing (it’s a long story). In a bravura sequence, her ‘10DDD floaties’ fill with air and propel her to the surface of the marina into which she’s dramatically thrown herself in an effort to unite her fractured family. It’s not an unequivocally positive result by any means – one breast deflates and the other swells enormously while she’s being resuscitated, and if anything the family tensions are made worse. But at least she’s mortified only in the modern sense, and not the archaic one.

We tend to sympathise more with the protagonists of YA cringe comedy than we might with a recidivist egoist like The Office’s David Brent. For one, the characters in teen fiction aren’t always the sole author of their own embarrassment. (And they’re not all as excruciatingly un–self-aware as Adrian Mole.) Sometimes they’re simply betrayed by their own changing bodies, or by other circumstances beyond their control. In Michael Gerard Bauer’s Don’t Call Me Ishmael, the main character is unfairly burdened with the name ‘Ishmael Leseur’. When the well-meaning Miss Tarango points out the connection between Ishmael’s name and Moby Dick, the connotations of the title of Melville’s novel prove irresistible to Ishmael’s classmates.

In John van de Ruit’s Spud, it’s not the family name that’s the source of embarrassment: it’s the family itself. By 5am on the morning John ‘Spud’ Milton is due to start at boarding school, his father has already assaulted the barking dogs next door with his supersonic rose sprayer (‘wearing only his Cricketing Legends sleeping shorts and a surgeon’s mask, to protect himself from the deadly chemicals that he’s now spraying into the atmosphere’). Later, during a buffet lunch at the boarding school, Spud’s (now drunk) father accidentally exposes the sausage rolls, gherkins, cocktail sausages and egg sandwiches Spud’s mother has been stashing in her handbag. To top it all off, Spud is a late bloomer. One of the duty prefects overseeing the boarding school showers describes Spud’s genitalia as looking like ‘a runty silkworm with an eating disorder’.

It’s been forty years since Margaret Simon and her friends chanted ‘We must - we must - we must increase our bust!’, but the adolescent experience continues to offer endless possibilities for humiliation. Which would be depressing, if humiliation were the only goal. It’s discovering how these resilient protagonists overcome their trials that makes them worth cringing through.