Clare Atkins on writing Aboriginal characters

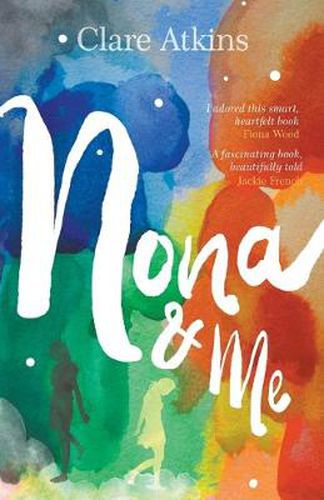

After several staff members read, and loved, Clare Atkins’ debut novel Nona and Me, we were excited to make it our Young Adult Book of the Month. Here, Clare talks on the challenges of setting a book in an Aboriginal community.

I suspect that many non-Aboriginal writers are scared of writing Aboriginal characters. I know I was. It is so easy to misrepresent. Or reinforce negative stereotypes. Or gloss over negative character traits in order to counter prejudice, and end up with a portrayal no one believes is real. My way around this, in writing Nona & Me, was threefold: I worked with a fantastic Yolngu lady; I wrote from Rosie’s perspective rather than Nona’s; and I gave up the idea that the book should be in any way ‘representative’.

When I came up with the story for Nona & Me my first thought was: ‘It would be fantastic if I could find a Yolngu author to co-write this with me. I could write from Rosie’s perspective and they could write from Nona’s. We could alternate chapters.’ But I quickly realised that if I tried to do this the book would never be written. Yolngu community members with the requisite English literacy and interest were already heavily relied upon; I didn’t want to be yet another Ngapaki person making demands on their time. So I approached a wonderful Yolngu woman and teacher, Merrkiyawuy Ganambarr-Stubbs, about working with me as a cultural adviser. She has written many children’s books in Yolngu Matha and was happy to help. I could not, and would not, have written the book without her input.

Yet, even with Merrkiyawuy advising me, I didn’t feel confident to write from Nona’s perspective. There is too much about Yolngu culture that I don’t – and, in some cases, can’t – know. And, logistics aside, I felt an underlying unease. I have given a lot of thought to this since. I have just read Omar Musa’s Here Come The Dogs; the author is Malaysian-Australian, but writes from the perspective of a Samoan. Not once did I feel this was inappropriate or culturally insensitive. On the contrary, it is fantastic to have cultural minorities on centre stage, to get to know them as people rather than cultures. I am half Vietnamese, and would love to read the story of a fellow ‘halfie’, even if the author is not one themselves. Yet I still wouldn’t feel comfortable writing from the perspective of an Aboriginal person. For me, this decision was linked with the history of white Australia taking from Aboriginal people – taking land, children, family, culture, art and stories. It was linked with the use of ‘black face’, theatrical makeup used to allow white people to portray, often one-dimensional or stereotyped, black characters. I decided I couldn’t write from Nona’s perspective – but I could write from Rosie’s, and the story of a non-Aboriginal girl growing up in an Aboriginal community was fascinating, confusing, unique and multi-dimensional in itself.

In writing about the community I resolved to just be honest. I poured my own experiences – and other people’s stories, gathered for research – into the novel. I tried to show the good and bad, the ugly and beautiful, and let the readers make up their own minds. Good YA fiction isn’t didactic, but it does get people thinking and talking. I let go of any notions that the story should be ‘representative’; that is just too big a responsibility, and it is paralysing for a writer. Instead, I focused on the story being personal. It is simply Rosie’s story, and it is just one story of many; it does not need to illustrate the whole history of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal relations in Australia. This was a liberating realisation. Instead of asking ‘What might happen in this situation between Aboriginal/non-Aboriginal people?’ I was simply asking ‘What would happen between Rosie and Nona?’

Along the way, I also found useful advice from Terri Janke in the Australian Society of Authors protocols for writing about Indigenous Australia. She said that, ‘if Australian writers are to depict a representative Australian society, they must write about Indigenous characters from diverse backgrounds, with good and bad attributes.’ This is what I’ve tried to do in Nona & Me. I hope you enjoy the book.