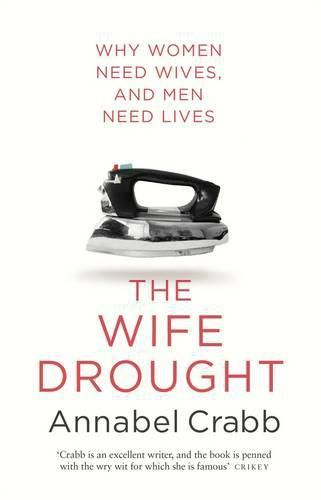

A conversation about The Wife Drought by Annabel Crabb

Having recently read Annabel Crabb’s The Wife Drought, our staff members Emily Harms (Head of Marketing and Communications) and Chris Gordon (Events Manager) chat about their experiences juggling work and family in relation to Crabb’s arguments.

Chris says:

I’m a dime a dozen. There are more women like me than not in Australia. I know this is true because I read about myself in Annabel Crabb’s excellent new book. I’m in my 40s (average age is actually 37), I work part-time in retail while my husband works full-time and I have got two kids (13 and 15). I’m tertiary educated, in fact have more qualifications than my bloke, but earn much less because when I had kids I made the choice to stay at home.

But Em, did you realise how unique you are?

Em says:

So you’re suggesting I’m a freak just based on this?

Well, you’re right in a way. As a female working full-time with a husband as the primary carer for my two kids at home (3 and 5) then, according to The Wife Drought, I am one of only 3% – yep that’s only 3% – of the Australia population. I know a lot of women think females are naturally better at the domestics of cooking, cleaning and washing than blokes but this certainly isn’t the case in my home. I would also go crazy being at home 24/7 with the kids whereas my partner really revels in it. No doubt that is why our set-up works.

And why do you think women with a helpful hubby or partner are supposed to feel as though they’ve won tattslotto, while for men with a helpful wife or partner it is simply a given?

Chris says:

Blokes need to talk up more about their relationships and their partner’s work. And we all need to teach our sons how to behave with emotional intelligence and with equitable action. We can change that view; we will change that view.

Em says:

I have a recent anecdote to demonstrate this point. My partner and I attended my son’s 3 and a half year check-up and the nurse was only talking to me about my son’s day-to-day activities. I explained that my partner is the primary carer. When she continued to talk to me about my son’s diet, I then added that he does most of the cooking too. She then turned to him and said, ‘Wow! You cook too!’

That comment would never be made to a woman as a primary carer so why the surprise when it’s the man?

Chris says:

That reaction from the nurse doesn’t surprise me. Just remember, 3%!

But, hey, don’t you reckon it’s strange how Annabel revealed that the more hours you work in the office, the more hours of housework you do? Apparently this isn’t even just a weird thing that happens in Australia, but all over the world, and it only applies to women. Blokes don’t have this problem. Annabel writes, ‘In an average Australian family, a woman will commonly behave like a housewife even if she isn’t one. And a man will behave as though he’s married to a housewife, even when he isn’t.’

Em says:

Go figure! I was completely outraged to read that: ‘even when mothers work full-time, they still do more than twice as much household work as their full-time working husbands. Forty-one hours a week compared to twenty!’ How did this disparity get so large?

Yet, I know I’m guilty of falling into this trap. Even as a full-time worker with my partner acting as primary carer, I certainly can’t say that I have a wife as such. When I am at home, I also do the cooking, the cleaning, the washing of kids, the homework, the school-related tasks. After a weekend I actually look forward to my commute on Monday morning where I can get some peace and quiet!

Maybe my need to stay active in the domestic sphere is out of guilt for not being at home like my mum was when I was little. (Though, the statistics in Annabel’s book state that working mothers spend more dedicated time with their kids one-on-one these days, than housewives did in the 70s and I’m happy to report that this reflects my experience.) Or maybe it’s peer pressure from the other mums I know.

I think Annabel hits the nail on the head where she says that there seems to be a feeling that working mothers should work as if one didn’t have children, while raising one’s children as if one didn’t have a job. To do any less, she says, feels like failing at both. This explains the constant state of tension and anxiety widely reported by working mothers. Have you ever felt this?

Chris says:

Motherhood for me opened so many doors I never knew existed. There is ‘Guilt Door’, ‘Time Negotiation Door’, ‘Martyr Door’ and ‘Anxiety Door’ (to name a few). And all these doorways certainly take up a lot of my headspace.

In The Wife Drought, Crabb has a chapter titled ‘Public Life? Need a Wife!’ where she talks about our present political landscape. She names who has children and who hasn’t, questioning the ‘why’ and ‘how’. Of course, the first name that springs to my mind is Julia Gillard who has mentioned before that if she had children, she wouldn’t have been able to achieve what she has.

Surely this would only be the case if she wasn’t receiving proper support.

Em says:

Can you believe it wasn’t until October 1966 that the Holt Government finally repealed the legislation and married women were freed to work in the public sector? Whereas, the married man was seen as a more valuable employee, with a stronger moral position from which to ask for a promotion of more job security.

Yet, regardless of how ‘unique’ I may be as a statistic in Australia, my partner and I do fall into the similar stereotype gender trap once we’re home with particular ‘specialisations’ – similar to how Annabel describes herself and her partner. For example, I keep track of birthdays, buy their presents and, when there is time, encourage the kids make the birthday cards. And my bloke fixes everything with the car and house, does the gardening and all IT-related maintenance when required.

What are the jobs you specialise in at home?

Chris says:

Em, I’m living the stereotype dream in that aspect, although I do all the gardening as well. My bloke also loves food shopping and so he does quite a lot of that, along with the cooking. Though I reckon he would struggle to tell you the dates of birthdays and social arrangements. He also does do all the IT and car maintenance while I do all the cleaning. It’s true that he doesn’t do more housework than I, but then he works more hours in the paid workforce. I’d consider us both as working full-time.

Em says:

In her book, Annabel says that most men fall into being the primary carer or wife through external factors rather than by choice. Your bloke was in-between jobs at one stage and was like a pig-in-shit running the household. How did this work for your dynamics at home, and did it balance things out on the domestic front?

Chris says:

Having my bloke around all the time was actually pretty hard work, although, admittedly, we ate really well during that time as he was forever cooking up a storm. He certainly did the lion’s share of domestic work as well and he loved hanging with the kids. But his priorities were very different to mine and I found that hard because I wanted him to do things my way, which I know is not fair at all. Then, when he went back to work, my kids and I really missed him.

Em says:

Do you think that time was beneficial for your bloke’s relationship with your kids though?

Chris says:

Without a doubt. My kids are teenagers now and they are both very close to their Dad. I’m sure it will be the same for your family. There will be no missing years. I reckon the older we get, the more grateful we will be for those times.

Em says:

Still, going back to that 3% … I find it odd that there aren’t more women like me who want to work full-time as a manager in the field they were trained in, and the industry of their choice. Is it largely because traditional masculine ideas – strong, hunter-gatherer, protector, bread-winner – still dominate in Australian society?

For an idea, just look at these responses from Australians in 1986, 2001 and 2005 who were asked: Is it better for the family if the husband is the principal bread-winner outside the home and the wife is primarily responsible for home and children? In 1986, 55% of men agreed, 30% in 2001 and then 41.4% in 2005. Meanwhile, in 1986 33% of women agreed, 19% in 2001 and then 36.4% in 2005. What’s going on here? I thought women’s rights were progressing over time not substantially regressing?

Why do you think this is? Do you think it’s in our biological make-up as women that we think that’s our primary role if we have kids? Surely things will change over time now that we’re living in the digital revolution where we have more freedom to conduct our work from anywhere.

Chris says:

I think that we are living in a time where parameters of behaviour are changing for both women and men. Given that humanity doesn’t enjoy change, it makes sense to me that we are reverting back to some earlier notions of what works and what doesn’t. It’s interesting looking at what’s happening in other countries. Crabb points out that in Norway the government has applied financial pressure to take parental leave for fathers, and the result is more fathers then spend more time with their children throughout their entire lives.

Personally, part-time work is the best choice for me right now. Crabb doesn’t go into this in her book but I reckon that living in this era of extreme information sharing, spending time with my kids doing very simple things – cooking, gardening, walking, reading – has become more essential than ever. I’m grateful that I work part-time so I can actually do both and I know I’m not alone in feeling this way. The ‘slow’ movement is having an impact on notions of success and that impacts on how domestic duties are seen. I think the reason that many women seem to look at powerful, high-pressure roles and choose no is because they don’t aspire to that world. They have a different definition of ‘a successful working life’.

So yep, I believe those statistics that indicate more women are choosing home life over highly-paid life. And I don’t think it has much to do with maternal instincts at all but rather, a sense of freedom. It is the result of a successful women’s movement, that these choices are respected.

Though, as Annabel points out in her book, I don’t think Australia has allowed blokes the same freedom to be creative regarding their careers, or simplify their lives. They need their own movement.