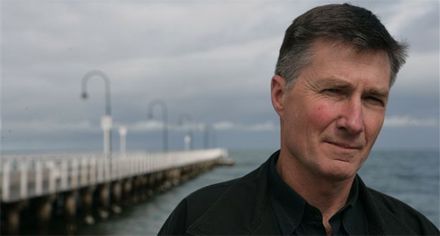

Garry Disher is one of Australia’s most popular crime writers, most notably over the past several years with his Challis and Destry series, set on the Mornington Peninsula. In Wyatt he returns to ‘old-style hold-up man’ Wyatt, last revisited 13 years ago, in response to popular demand – and it’s a beauty.

The Wyatt series is told from the point of view of a criminal who the reader can’t help but root for. This type of book seems to be increasingly popular at the moment, with the success of the

Crime-from-the-inside films and novels might be growing in popularity now, but they’re not a new form. I wrote the first Wyatt novel 20 years ago, drawing on an American hard-core tradition of 50 and 60 years ago. I think Wyatt and Dexter are popular because they appeal to our darker sides. Obviously most of us won’t pull the perfect robbery or kill those who’ve done us wrong, but we need to be able to imagine doing it. Most of us are hemmed in by doubts and scruples, our lives seem subject to random forces, and so it’s liberating to follow characters like Wyatt and Dexter as they impose a kind of order and, without guilt, do the things we wish we could do.

Wyatt is ‘an old-style hold-up man: cash, jewels, paintings’. He avoids the drug scene and is restricted in what he does by the fact that new technology has outstripped his expertise. Is there a certain appeal in writing an ‘old-style’ criminal like him? Does this add an extra challenge for you when deciding which situations he’ll be embroiled in, and how he’ll deal with them?

It’s probably beyond my skills to create a loveable drug dealer. The face of crime has changed with drugs. There’s a greater chance of viciousness and unpredictability when greed, addiction and huge profit potential are involved. Besides, it’s more fun, and somehow more worthy, to show Wyatt holding up a payroll van rather than ripping off an addict or a dealer. The problem for me (and him) is finding ways to get the cash without having to hire a dozen guys with specialist technical know-how and gadgetry, not to mention showing the reader how it all works.

Your books – both the Wyatt and Challis and Destry series – are often very Melbourne in tone. Wyatt evokes a range of city locations, from Frankston’s teenage mothers, to dodgy stallholders at the Queen Vic markets, architectural monstrosities in Mount Eliza and young yuppies in Southbank. How important is place to your writing?

Setting should be a vital element of all fiction and it’s crucial in crime fiction. From a writing craft point of view, I can’t see the characters until I see the ground they walk on, and vice versa. Setting is useful in all kinds of ways: adding to our sense of the characters, creating an appropriate mood (e.g., distress), appealing to our senses (we’ve all had a bus belch on us), and, more broadly, showing the social as well as the topographical diversity of a region.

Wyatt

Although there’s a common pattern to the Wyatt novels (as there is with the Challis and Destry novels), I use subplots and minor characters to mask it. The story arc is simple: Wyatt identifies a job, is betrayed before or during the robbery, and gets his revenge (and the gear back) at the end. Sounds simple, but I can spend months planning these novels, balancing personality traits with plot demands, and carefully placing the sudden reversals and partial resolutions. And all this so the whole thing feels organic rather than contrived before I start. But when I write, I always listen to the niggling voice that takes me away from the plan.

Your crime novels are engrossing reads that are pretty faithful to the genre, but are notable for being interwoven with sly, often very funny, political and social observations. In

One of crime fiction’s great strengths is telling us about the world we live in. It’s a barometer of prevailing social tensions. It casts an unimpressed eye over the powerful. Most ‘literary’ novels let us down in that regard. Nevertheless, putting the boot in must always come second to the storytelling.

This is the seventh Wyatt novel, coming after a long hiatus. What made you decide to bring Wyatt back – and are you planning an eighth?

I think writers need to keep refreshing themselves. After writing the first six Wyatts, I needed a break. But Wyatt was always alive in the back of my head, and I was always being asked what had happened to him, and another novel was needed for the German market, where Wyatt is very popular.