Craig Silvey

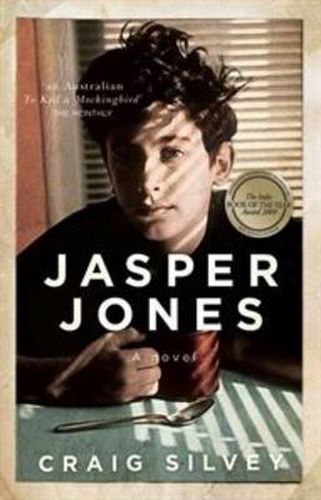

Craig Silvey started his career with a bang with his first novel, Rhubarb. Seven years later, his new nove*l, Jasper Jones, *has the literary world abuzz. Tony Birch spoke to him for Readings for our New Australian Writing Feature Series.

Craig Silvey’s first novel, Rhubarb, was published to critical acclaim in 2004. The excitement surrounding the book’s release quickly spread from his home state, Western Australia, to the eastern seaboard. The reception and following success of Rhubarb resulted in Silvey receiving a prestigious Sydney Morning Herald Best Young Novelist award in 2007. Those who have been eagerly awaiting a second novel from Silvey will be pleased. Jasper Jones is an engrossing and immediate page-turner that evokes an influential literary history while producing an original and rewarding narrative in its own right.

The story is set in the fictional WA rural town of Corrigan in 1965, and begins with the rattling at a bedroom window in the dead of night, the mysterious death of a young girl, and the murky secrets held in the bottom of a swamp. The tragic circumstances that follow this eventful night involve the outcast Jasper Jones himself, a ‘mixed race’ boy, born of shame, secrecy and town gossip, and a pair of self-imposed internal exiles of Corrigan. One is the young teenager, Charlie Bucktin, the narrator of the novel, while the second is his closest friend, Jeffrey Lu, a boy of Vietnamese background, who confronts the racial taunts regularly hurled at him with a razor-sharp intellect and the genius of a pull shot to the boundary.

Corrigan is a town steeped in mystery, where the barely hidden secrets and whispers of the past litter the landscape. It is also a place wrought by tragedy and loss; a theme explored in the book through the emotions, thoughts and exchanges between Charlie and Jasper. While Charlie in particular is racked with guilt and despair over his own actions as well as those of others, he also articulates a poignancy and tenderness beyond his years on realising that he must confront his own dishonesty.

While the aggression of Corrigan is often apparent, it is the potential for violence pervading the town that provides a relentless tension throughout the book. I was particularly struck by the degree to which past actions haunt the contemporary landscapes of town; whether it be through the fragile relationships within families, the sense of shame and subsequent secrecy that can destroy the concept of love itself, and the inability of a community to cope with and accept difference, rendering notions of the communal redundant.

I was also interested to what extent the fictional Corrigan might reflect the realities of life in rural WA. Silvey, while drawing to some degree on his own experience growing up in a somewhat similar place to Corrigan, had no desire to write a book that was parochial. He is interested in universal themes that reflect and question a wider experience than his own, and those conveyed through and possibly restricted by the ‘regional’ novel. With the writing of Jasper Jones, he wanted ‘it [Corrigan] to be recognised as a country town that could be anywhere in Australia. I would hope that it reflects a broader Australian experience’.

The novel leaves us with important questions to ponder about the ‘Australian experience’. In discussing this theme in the book, Silvey speculates on whether Australia really did ‘come of age’ during the 1960s, the period when the book is set, as is often claimed by social commentators. Or did we instead ‘learn to be adult, rather than grow up?’ (For the author, there is a subtle but important difference between the two ideals.)

Questions such as this are testament to both the creative and intellectual range of this novel. Or to put it more simply, Jasper Jones contains a sharp and lively narrative drive found in all great storytelling (no doubt assisted by a superb and authentic use of dialogue), while inviting us to reflect more deeply on the qualities and flaws of the human condition.

While covering the familiar territory of the coming-of-age novel, Silvey projects some fundamental moral questions onto each of the teenage boys, who in various ways represent for the author, ‘what it’s like to grow up smart or poor or Asian or black or shy or tentative in rural Australia’.

Personally, I identified with the young Jasper Jones, in particular. I loved his cheek and his courage, as much as I felt dismayed by the saddened circumstances of his life. To some degree, Jasper represents those people who are too often ostracised by the wider community. Those who, based on Silvey’s own experience of living in a rural town, become ‘the fall-guy, an easy target’, often held to blame for all the ills of a town. ‘It seemed that people were assigned these character categories,’ Silvey reflects, ‘which they could not free themselves from once they were in place.’

Jeffrey Lu and his parents are also outsiders. They are a Vietnamese family living in a country town when Australia itself is in conflict over a war being fought elsewhere (a reiterated theme of Australian history). Jeffrey is often abused, and appears to accept his mistreatment with undue deference – until he conjures his (sweet) revenge. Which is not at all surprising, having since discovered that Craig Silvey feels that ‘Jeffrey may well be my proudest literary creation’.

No character appears to be a comfortable insider in the town of Corrigan. While Jeffrey and Jasper are clearly marked as outsiders, discomfort and alienation visits most everyone in the town. There is the mysterious Mad Jack Lionel, a seemingly dangerous ‘village idiot’ archetype who has a far more complex story to tell; Charlie’s parents, who are all but estranged from each other from the outset of the novel; Eliza Wishart, a girl Charlie falls in love with, who just can’t wait to defy her parents; and the local gang of ratbag teenagers, whose attempts to bully and humiliate Charlie and Jeffrey serve only to highlight their own marginality.

Jasper Jones is also a book about first love and the depth of friendship that can hold outsiders together when faced with adversity. It is also unashamedly a book about books. Those of us who have read throughout our lives will appreciate, as Charlie Bucktin does, the sustenance of the soul that comes with reading – and re-reading – favourite novels such as To Kill A Mockingbird (the themes of which resonate subtly throughout Jasper Jones). These books were the emotional security blankets that nurtured us through difficult times as teenagers. Therefore, we remain fiercely loyal to the fictional characters that subsequently became our lifelong companions. This is a sensibility that Silvey and his own fictional companion, Charlie Bucktin, are acutely aware of.

Holden Caulfield and Huckleberry Finn make cameo appearances in Jasper Jones, as does Atticus Finch himself, the quintessential fictional father figure that many of us longed for as teenagers. Atticus is both a tower of strength, and the loving and wise parent. (This idyllic image was enhanced further, of course, when Gregory Peck became Atticus on screen.)

It is obvious that Charlie sees something of Atticus Finch in his own father, a quiet and reserved man, who both introduces his son to the world of books while secretly scratching away a novel of his own, Patterson’s Curse. Silvey explains that it is ‘literature that provides Charlie with his own method of escape’, not only from the landscapes of his country town, but the emotional predicament he subsequently finds himself in. Charlie escapes into ‘his own mythologised utopia, a place where intellect is praised, where writers are beloved and books are revered’. Amen to that.

Jasper Jones is a wonderful book, containing an ensemble cast of rich characters and several sub-plots that maintain their own level of enthralling drama. And overlaying the lot is one of the major issues of experience, of life, found at the heart of all good novels. For Craig Silvey, ‘it’s about that moment where the bubble is burst and you’re suddenly exposed to the real truth of things and the blind trust of childhood dissolves’.